Terry Atkinson

The Books are Very Nearly Cooked

March 7 – April 13, 2024

Photography: Julian Blum

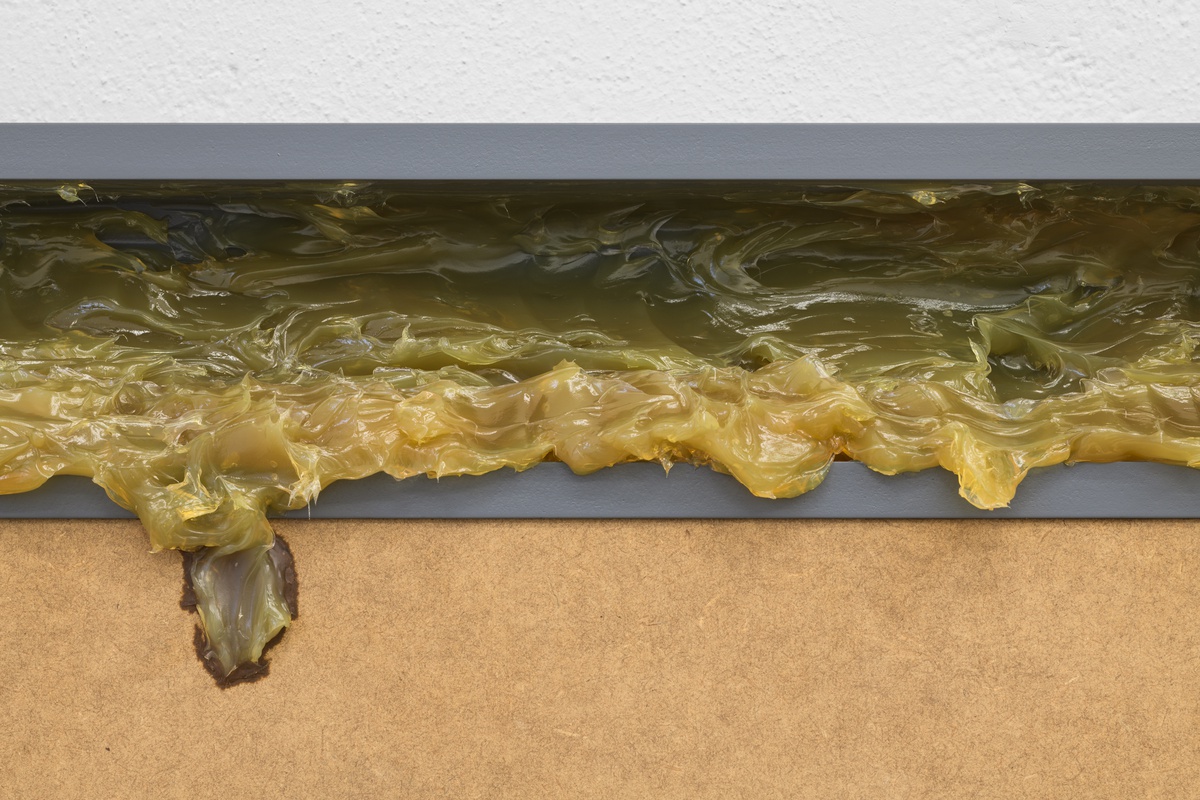

Terry Atkinson, GREASE-FALL, 1990/2024

wood, varnish, grease

97 × 150 × 24,5 cm

Terry Atkinson, GREASE-FALL (detail), 1990/2024

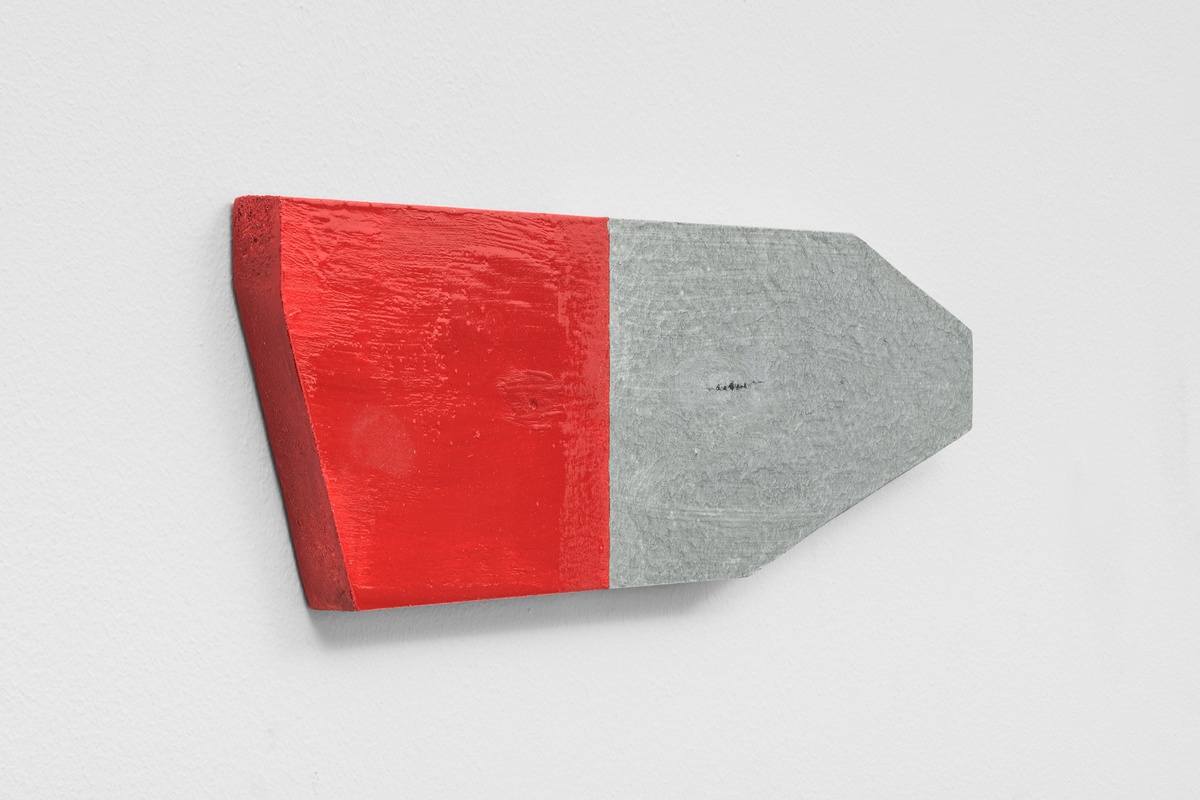

Terry Atkinson, Red/Silver Enola Gay Axe Head Mute 2, 1991

metal paint on board

10,4 × 34 cm

Terry Atkinson, Red/Silver Enola Gay Axe Head Mute 2 (detail), 1991

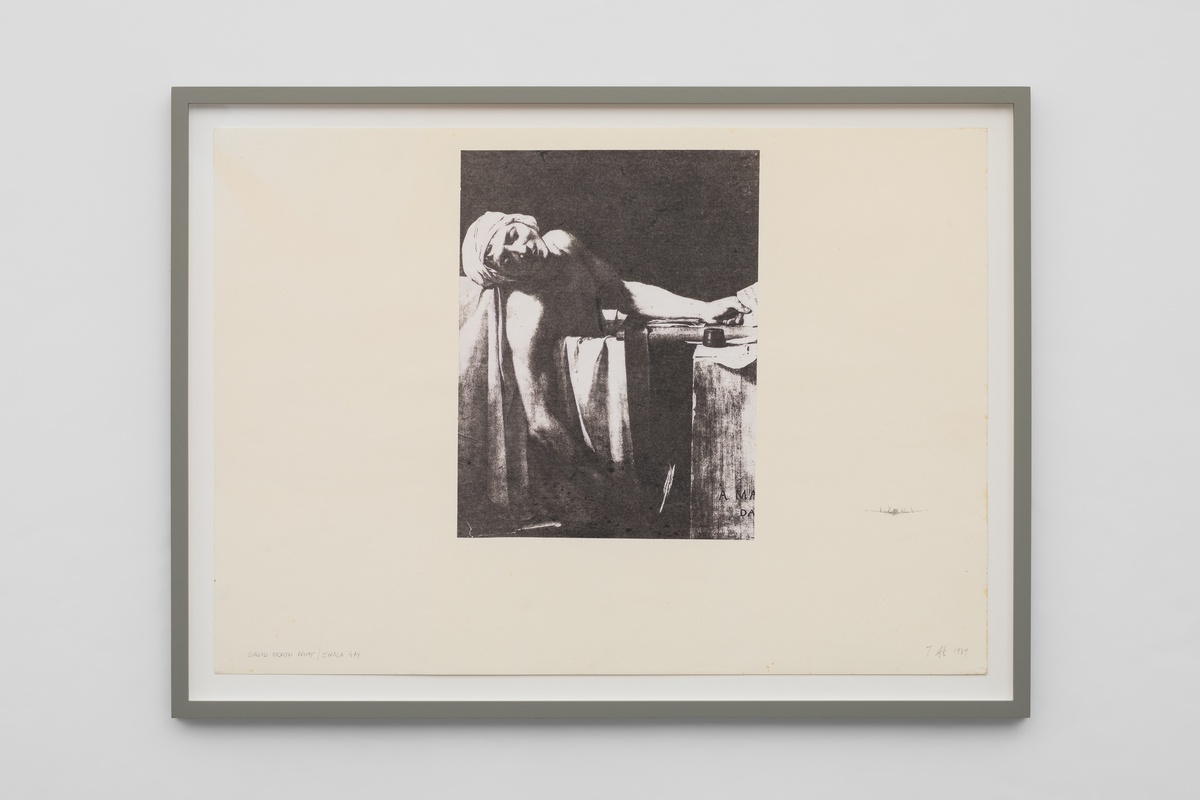

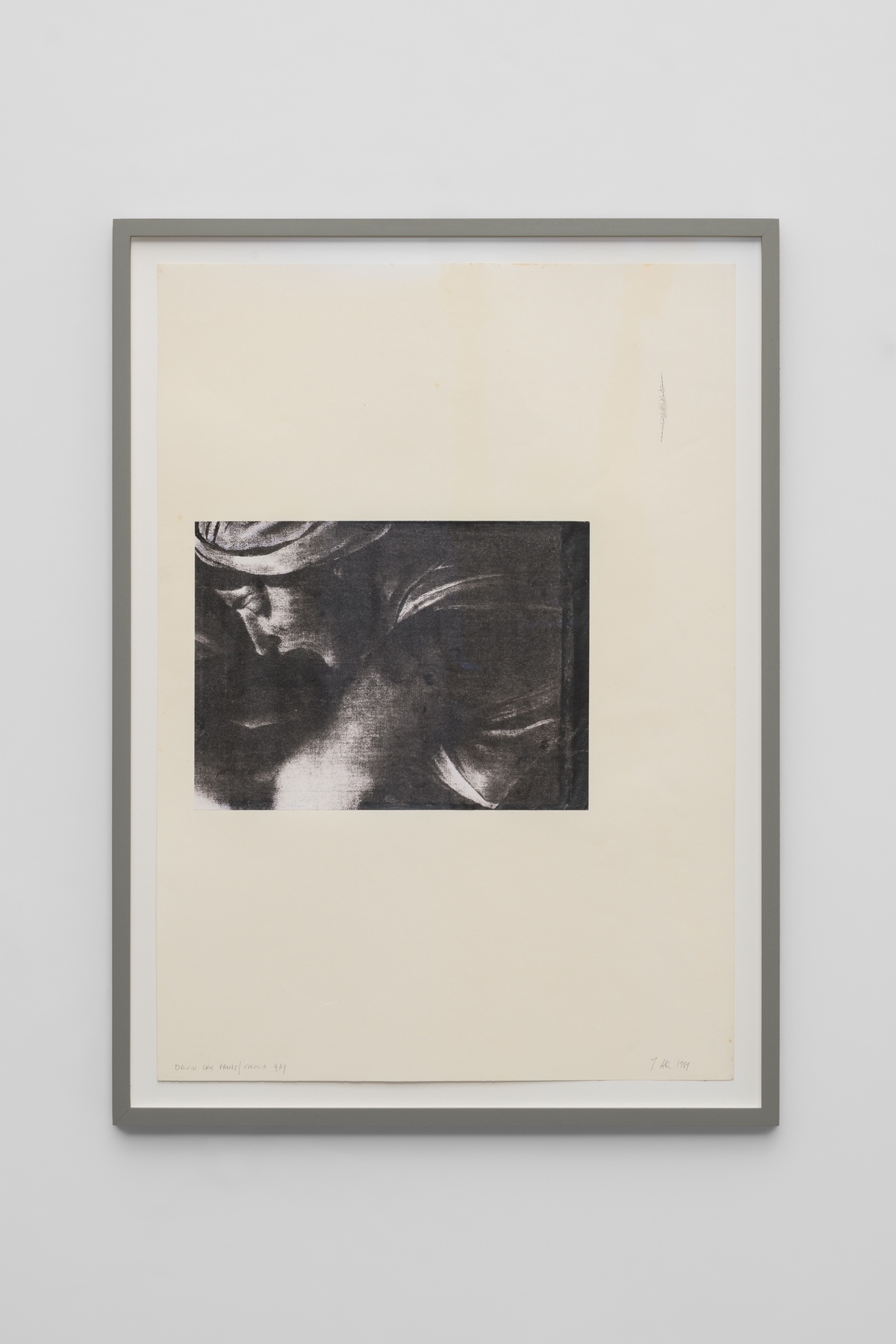

Terry Atkinson, David Death Print/Enola Gay, 1989

transfer print on paper

42 × 59,4 cm

Terry Atkinson, David Death Print/Enola Gay (detail), 1989

Terry Atkinson, Grease Work into Enola Gay, 1990

grease, paint, on composite board

123 × 154 cm

Terry Atkinson, Grease Work into Enola Gay (detail), 1990

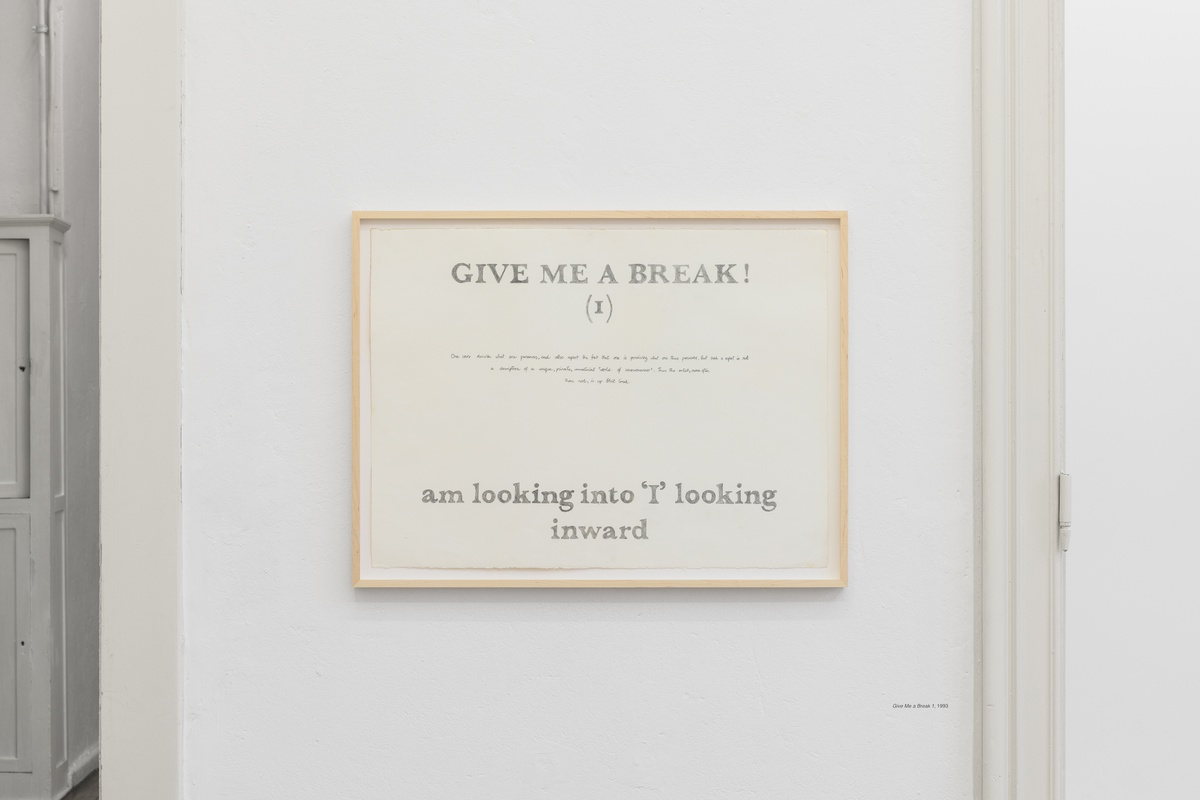

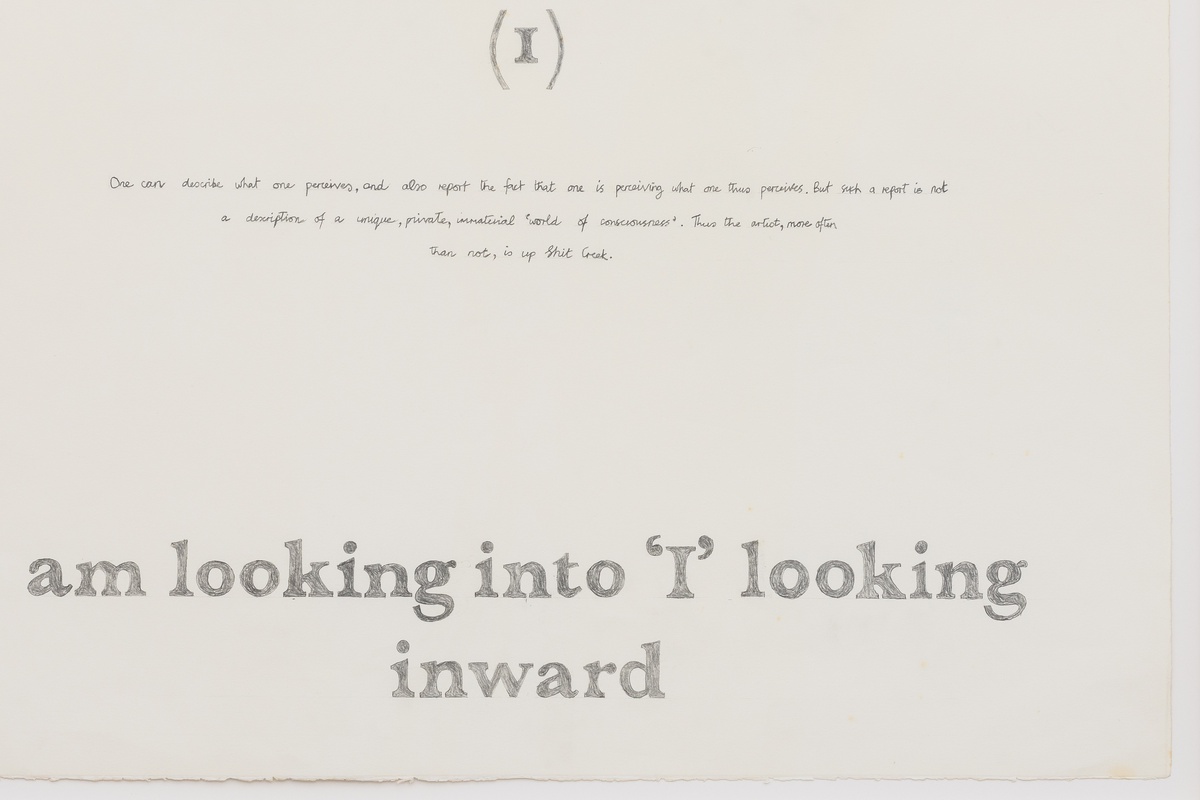

Terry Atkinson, Give Me a Break 1, 1993

pencil on paper

56,6 × 76,5 cm

Terry Atkinson, Give Me a Break 1 (detail), 1993

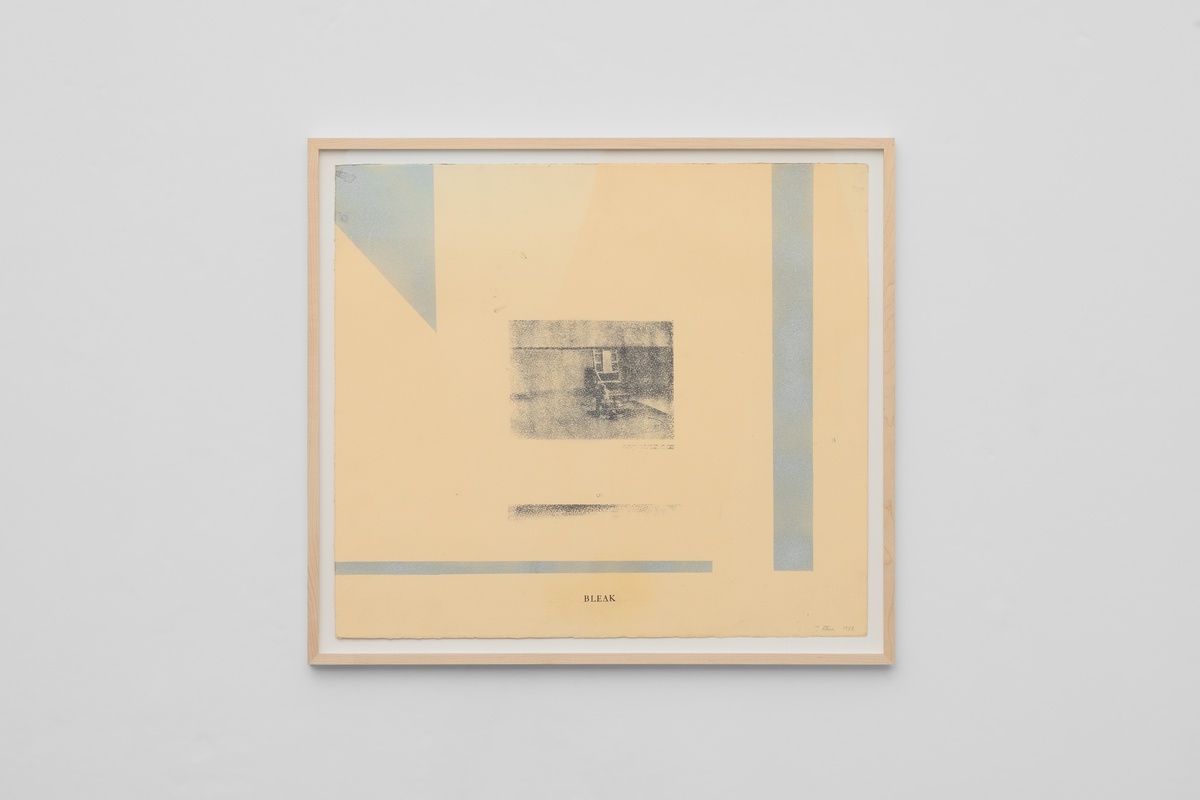

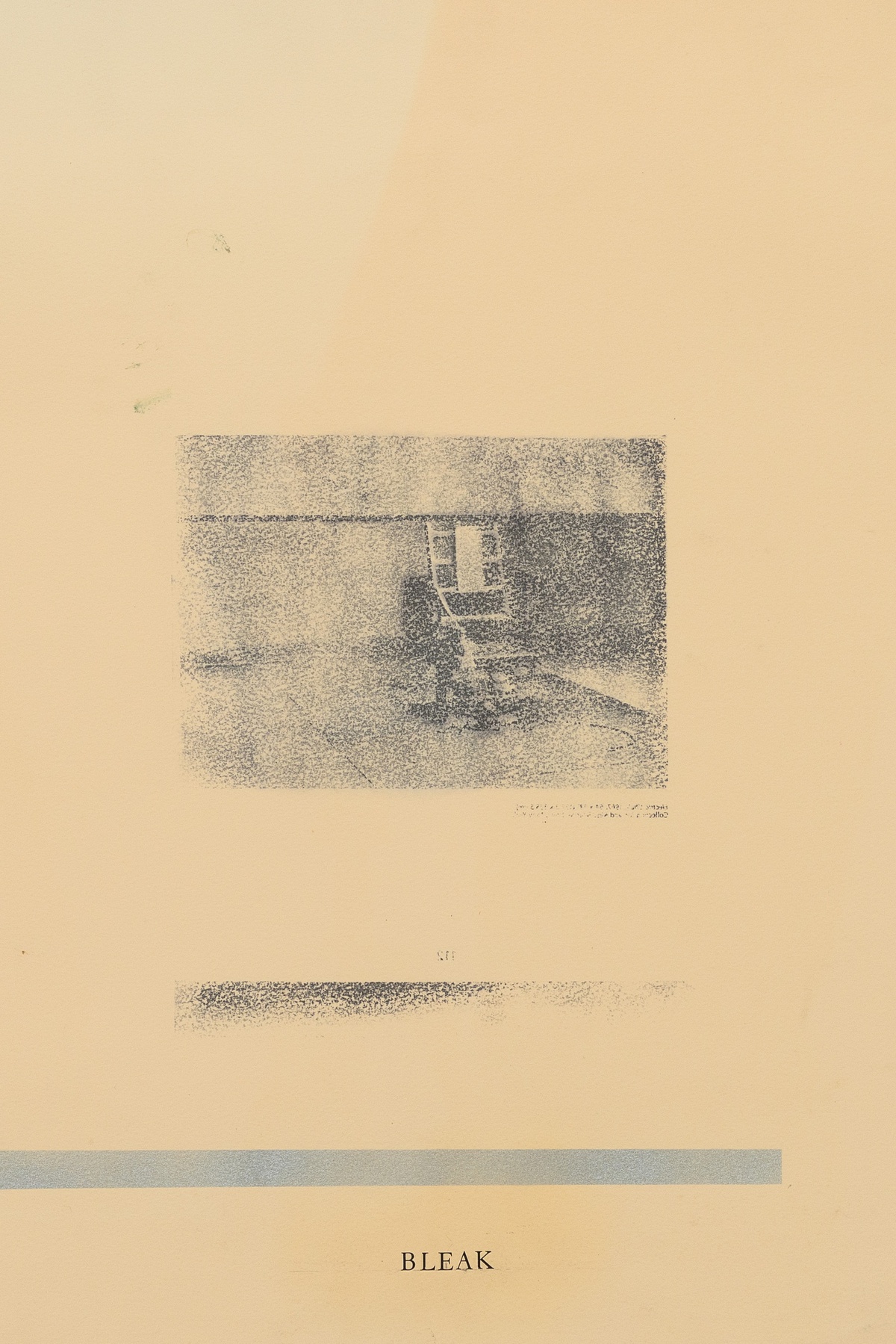

Terry Atkinson, Bleak, 1988

transfer print and silver paint on paper

55,3 × 62,3 cm

Terry Atkinson, Bleak (detail), 1988

Terry Atkinson, Hammerite Gold Enola Gay Mute 1, 1988

metal paint on board

10 × 19 cm

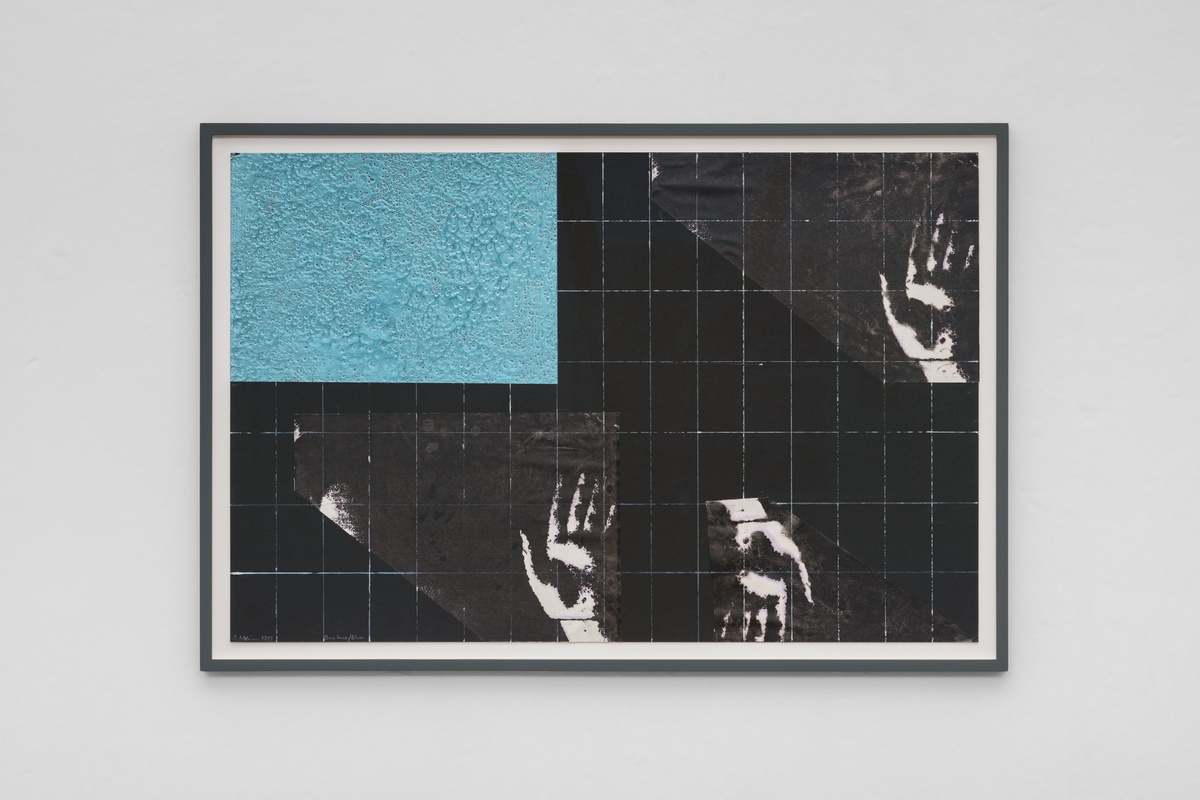

Terry Atkinson, Black Hand/Blue, 1990

acrylic, transfer print and metal paint on card

53,1 × 81,2 cm

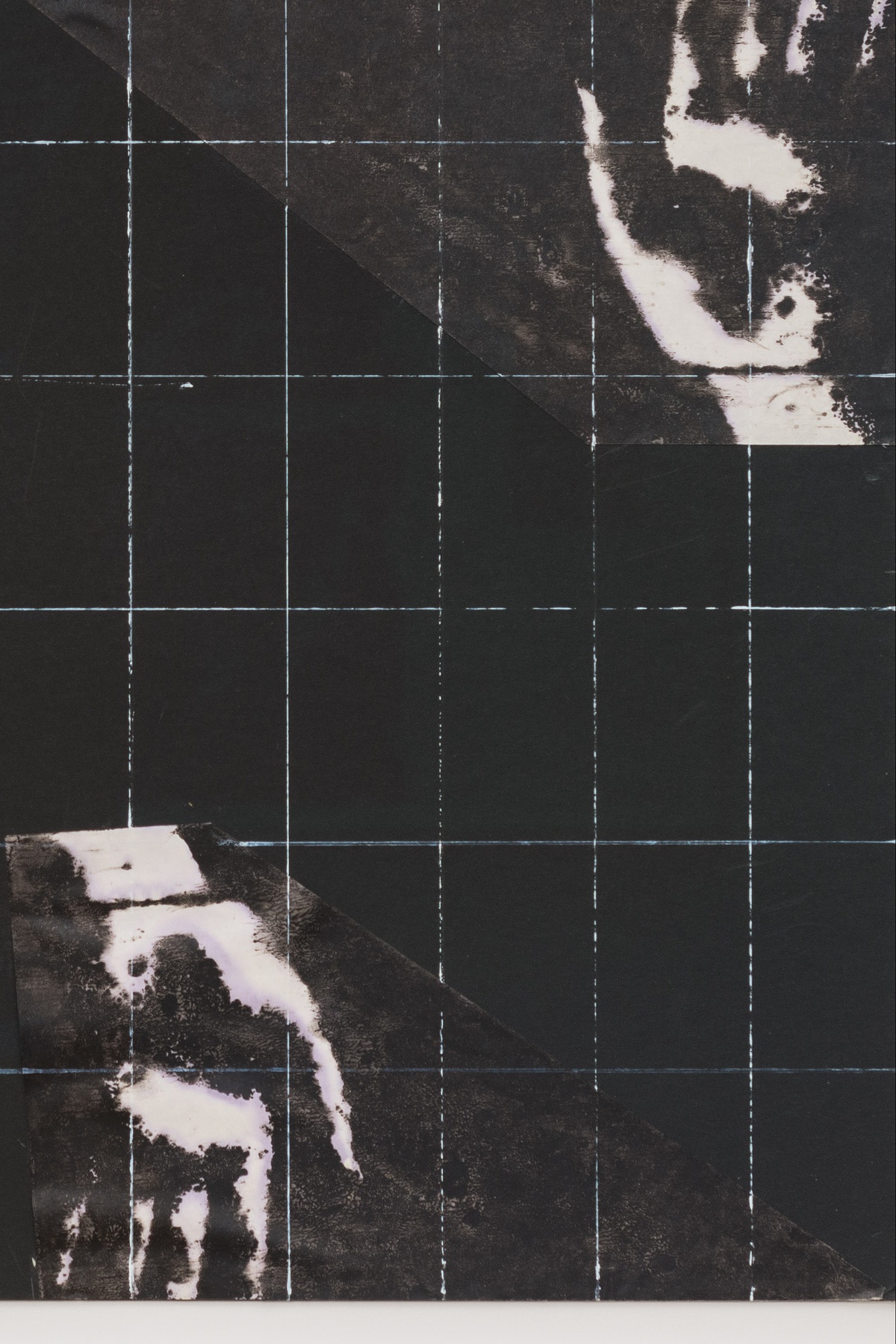

Terry Atkinson, Black Hand/Blue (detail), 1990

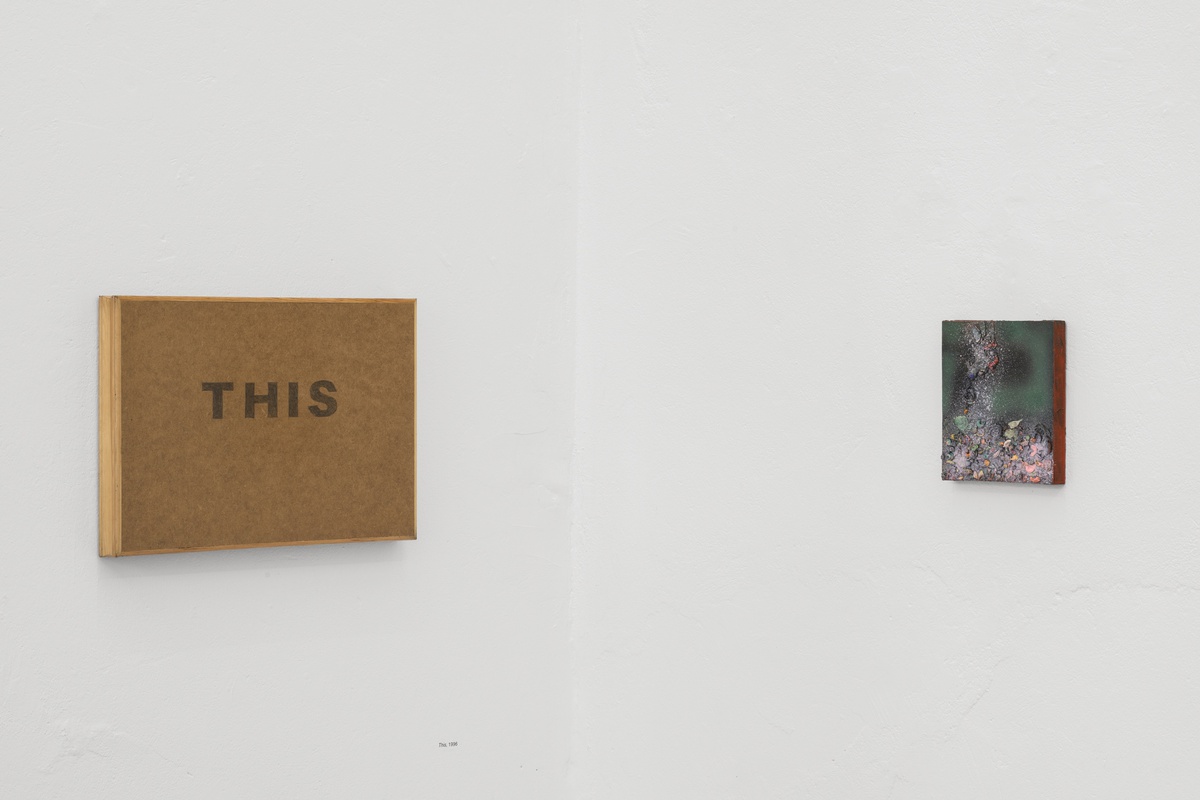

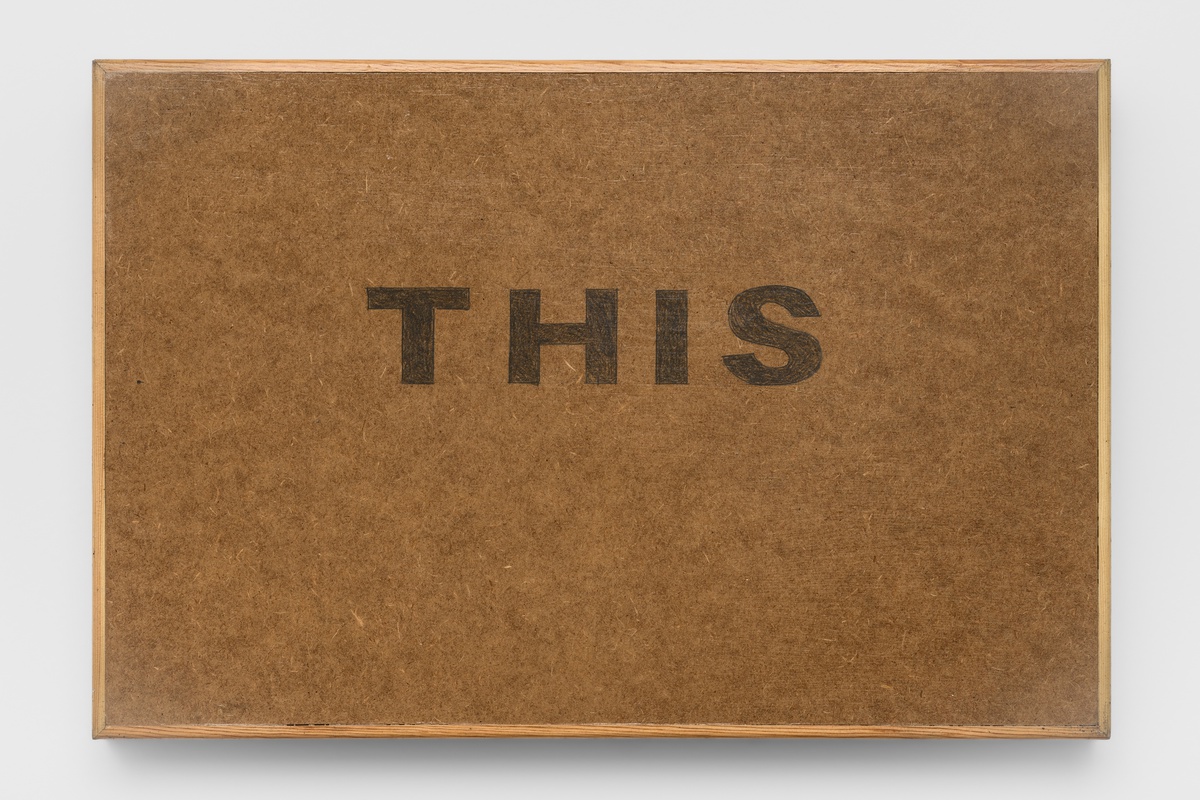

Terry Atkinson, This, 1996

pencil on board

36,8 × 55,2 cm

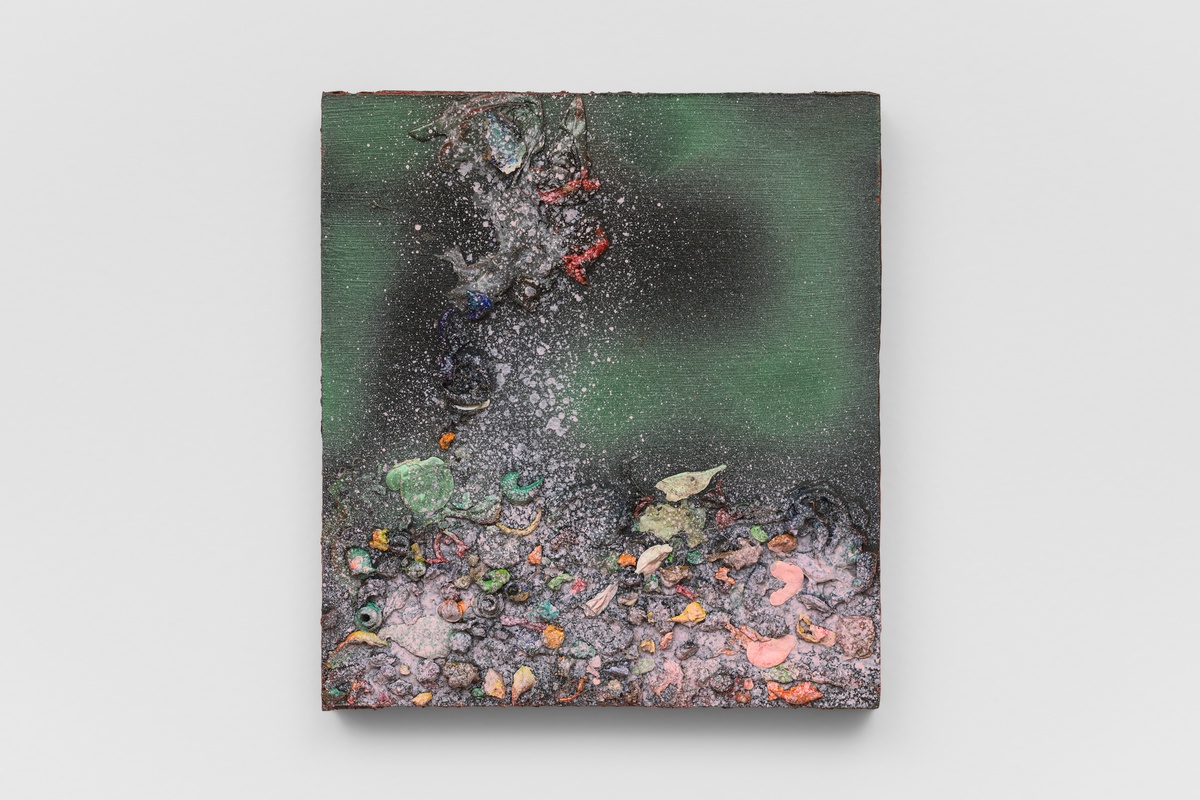

Terry Atkinson, Map of Paint Island 3, 1986

mixed media

21,5 × 20 cm

Terry Atkinson, Booby Map 7, 1997

mixed media

23 × 23 cm

Terry Atkinson, Pox –Head, 1984

mixed media

21,8 × 15 cm

Terry Atkinson, Brown-Bronze Enola Gay Axe-Head Mute with Grey Enola Gay, 1990

metal paint on board

60 × 80 cm

Terry Atkinson, Brown-Bronze Enola Gay Axe-Head Mute with Grey Enola Gay (detail), 1990

Terry Atkinson, A Reading of David (Ruse), 1989

transfer print and metal paint on paper

59,4 × 84 cm

Terry Atkinson, A Reading of David (Ruse) (detail), 1989

Terry Atkinson, David Cry Print/Enola Gay, 1989

transfer print on paper

41,6 × 59,2 cm

Terry Atkinson, David Cry Print/Enola Gay (detail), 1989

“Is writing ‘painting is dead’ the same as painting ‘painting is dead’?” reads a work in Terry Atkinson’s series Give Me a Break (1993). But what exactly does it mean to read a painting? Would one read a painting the same way one might read a book? And when that painting is of a text, does that change how one would read that painting? Long beyond his departure from Art & Language,Terry Atkinson continued to perform experiments on image/text relations, investigating different ways of looking, of reading, and more generally on the transmission of knowledge. But beyond a purely analytical inquiry, Atkinson’s interest lies in challenging the assumption of the purely visual outside of language, l’art pour l’art, that perpetuates the myth of an autonomous field of art divorced from worldly and sociopolitical contexts. If everything within Atkinson’s decades of practice is a potential subject of its own critique, questioned and deconstructed in constant endosmosis, all is bound by the underlying axiom that there is no such thing as art outside of language or art devoid of ideology.

Not even a decade after its founding in 1968, the conceptual collective Art & Language had become more or less subsumed into a canon of avant-garde art production it had set out to position itself against.After participating in documents 5, curated by Harald Szeemann (1972) and its transatlantic expansion to include new members such as Joseph Kosuth, Ian Burns, and Mel Ramsden,Atkinson’s departure from the collective was by no means a return to the singular artist-genius but instead motivated by the shift of the social dynamic from “that of a group to a caucus.” In a self-declared break with conceptualism, Atkinson saw the movement emptied out of its critical and philosophical parameters, reduced to little more than a gesture or style.The works that followed carried his own signature or that of one of the many pseudonyms he worked under:Teresa Actor,Terry Actor, Terry Enola Gay,Terry Dog, remaining faithful to the elusive, dispersed artistic produce. From the mid-1970s onwards,Atkinson’s main focus was the critique of the artistic subject and the reflection on the conditions of production for avant-garde art.

The works shown at Schiefe Zähne span various series made from the 1980s and 1990s, comprising textual, material, and image elements. Throughout his decades of production, Atkinson uses a number of recurrent subjects that intermittently interlock, creating hybrids that have been discussed as a method of “betting and trying,” or analytical and semantic experiments exercising the boundaries of a field stamped out by Atkinson since the 1970s. Compared to his oeuvre at large, one may perhaps be inclined to say that the works on view at Schiefe Zähne are amongst Atkinson’s least explicitly political, more focused on the philosophical or semiotic conditions of art-making. Compared to recent drawing series, in which Atkinson has used social-realist and figurative drawing,often depicting scenes of war or social injustice,the works here are not necessarily immediately visible as having a political agenda or contents. But Atkinson would probably chuckle, if not frown, at such a remark, countering that there is “no such thing as non-political art”, a belief that further catalyzed his departure from the conceptualist avant-garde.

The Enola Gay series aims at this exact issue, taking as its subject matter the genre of the monochrome. Perhaps the pinnacle of formalist pure painting, allegedly transcendent of representation, the uniform field of color is broken through Atkinson’s addition of a painted aeroplane. Barely more than a fine, ragged line, the plane is not immediately recognizable as an object at first sight but soon transforms the all-over field of color into a horizon.

The Enola Gay machine made history as the machine that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.With the addition of the plane and the text title which necessarily visually accompanies the viewing experiences, the historical drama is almost stamped onto the surface. By juxtaposing an image of such an ominous technology within what appears to be an autonomous field of abstract art,Atkinson underscores the notion that Modernism arises as a product of those same circumstances that gave rise to the creation and deployment of nuclear warfare. In “Grease Work into Enola Gay” (1990), the areoplane is no longer the small tear in the canvas but a large and looming threat.Atkinson started using grease as a volatile material that was hard to contain as a substance that was constantly changing, reacting to its surroundings. In pursuit of the deconstruction of his artistic subjectivity, grease seemed to offer a mode of continuing the process of production beyond the premise of the artist’s studio. During the exhibition, the grease works are in constant metamorphosis, dripping, oozing, melting.

Besides the monochrome, existing works of art crop up at various points in Atkinson’s work, like Andy Warhol’s electric chair in“Bleak,”or the reoccurring motifs of 18th-century history painter Jacques-Louis David.Pursuing the question “how to represent the representer?”Atkinson takes a step outside of his discipline of history-telling into the field of historiography, formulating a critique towards the unrecognized method of documenting and telling history. Interested in the artist’s position as a maker of history, a teller of stories, one is compelled to ask how cultural production is entangled with official, hegemonic histories.“Ruse,” meaning trick, is often added as a title in combination with David’s history painting, playing a sort of naming-game. Using conventional visual language, Atkinson transfer-prints and obscures the heroic scenes painted by David, to create something that looks like we think art should look like.Again,Atkinson’s analytical questioning comes into play:Is it possible to make something that looks like art but isn’t? What and who gets to decide such matters? Does the “trick” lie solely in the addition of the title, designating the work as such?

Visibly titling each work has become an integral part ofAtkinson’s exhibition making,as a deliberate intervention against the purely visual sensation of looking at art. Each accompanying title is matter-of-fact descriptive to the point that its dryness becomes comical, raising the brute materiality of language to a point at which it may be easily inspected rather than poetically consumed.According to the artist:“The more text, the better.” Over the years, it is as if Atkinson has crafted his own semiotic web, a language through the various signs and signifiers he brings together to see how they interact with each other. Enola Gay and David, or Enola Gay through Greaser, Grease and Bunker Slit; this idiosyncratic vocabulary continuously reflects the condition of its own production, counteracting any attempt of self-mythologization.This exercise of betting and trying of an artistic model that may pose an alternative to that of the artist as the driver of cultural production, perpetuating the need for newness in a capitalist system reliant on expansion masked as progress.With less of a definitive answer but a by now well-stamped-out field of interrogation,Atkinson is aware of the incongruous space he occupies, “articulating a dynamic between the reactive, the predictive, and the speculative.”

Maybe the answer to the question – if writing and painting “painting is dead” is the same – is already answered in the same breath it is asked.Despite all the urgency and sincerity,Atkinson never gave up on humour,as he brazenly exclaims: Give Me a Break!

Terry Atkinson (b. 1939 in Yorkshire, UK) studied at Slade School of Fine Art and was one of the founding members of Art & Language in 1968, as part of which he exhibited at documenta 5 (1972) curated by Harald Szeemann.After leaving the collective in 1974, Atkinson went on to exhibit at theVenice Biennale in 1984 and was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1985. He lives in Leamington Spa, England with his wife, Sue Atkinson, with whom he has frequently collaborated