Matthias Groebel

the rhythms of reception

April 30 – June 4, 2022

Photography: Cedric Mussano

Matthias Groebel, L0597, 1997

acrylic on canvas (computer-assisted painting)

95 × 95 cm (3) + 95 × 45 cm (2)

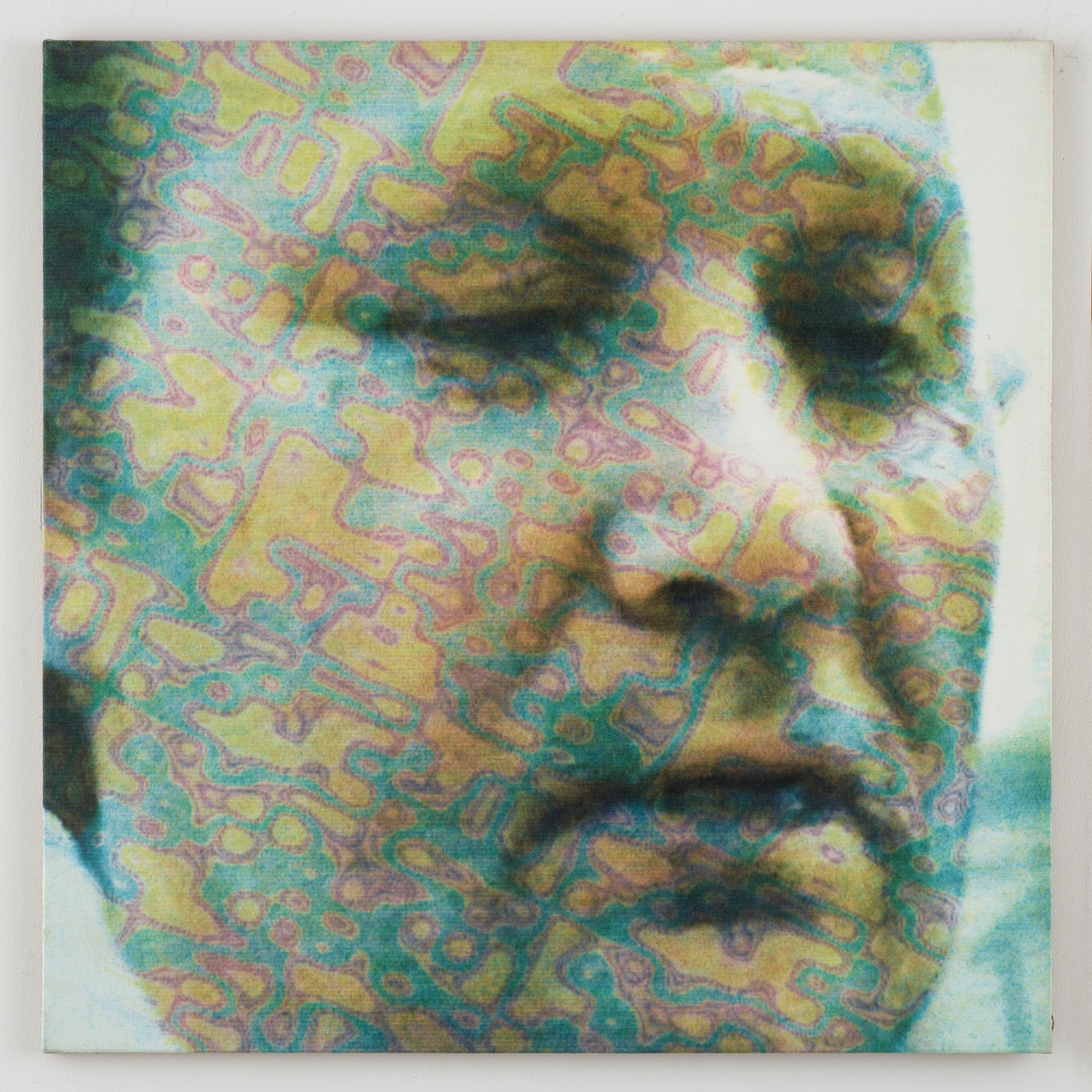

Matthias Groebel, L0597 (detail), 1997

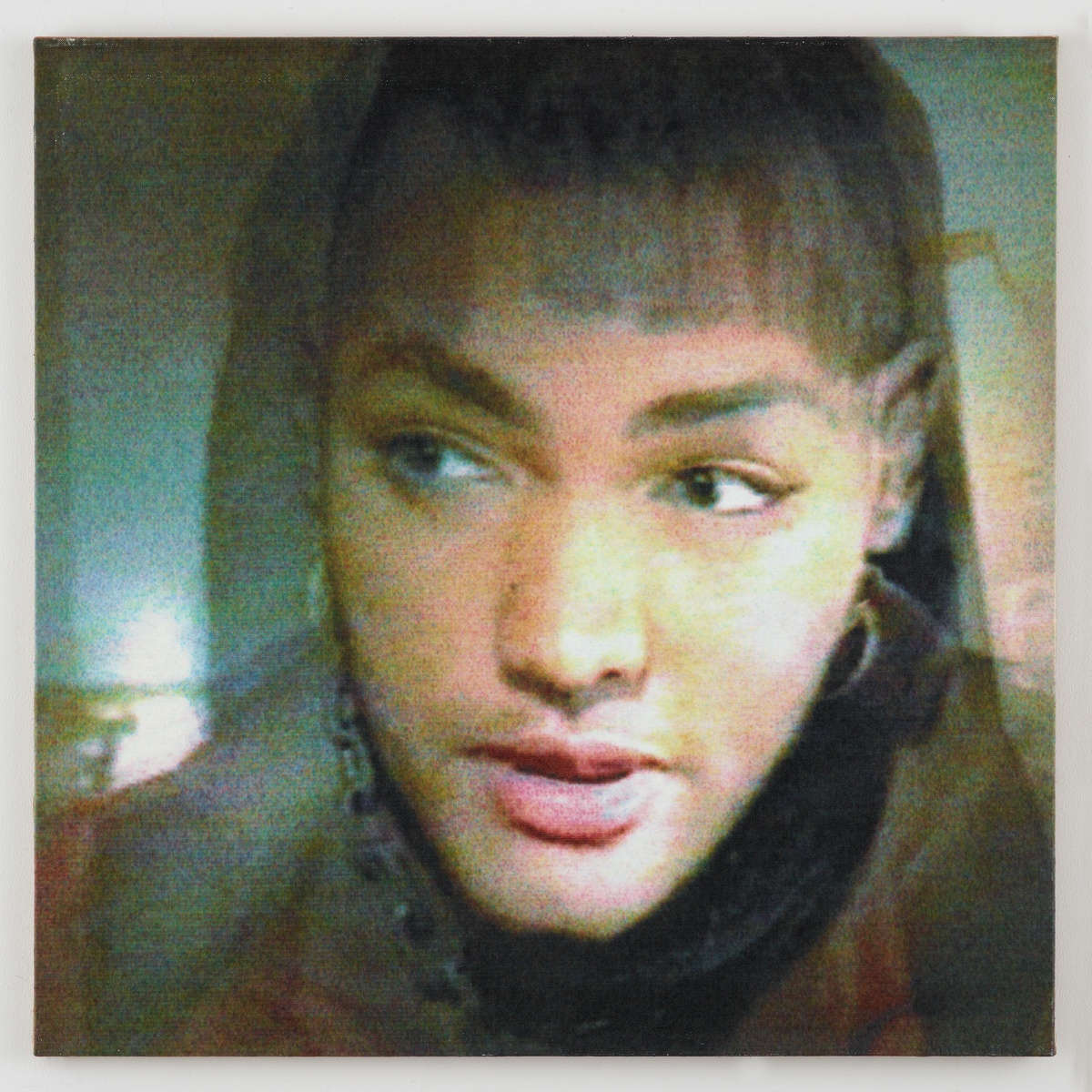

Matthias Groebel, Untitled, 1994

acrylic on canvas (computer-assisted painting)

95 × 95 cm

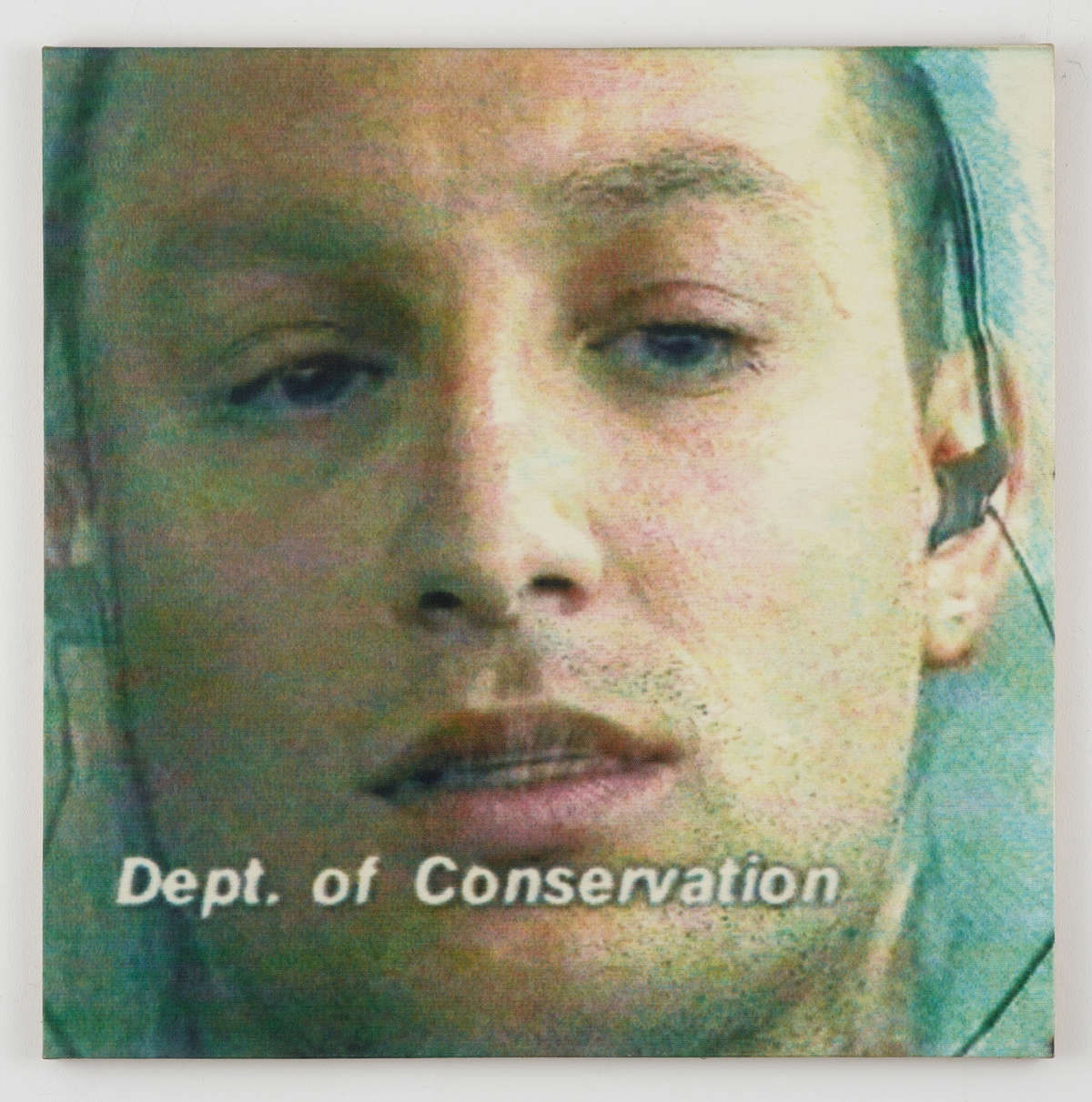

Matthias Groebel, Untitled, 2003

acrylic on canvas (computer-assisted painting)

95 × 95 cm

Matthias Groebel, Untitled, 1994

acrylic on canvas (computer-assisted painting)

95 × 95cm

Matthias Groebel, L1095, 1995

acrylic on canvas (computer-assisted painting)

95 × 95 cm

Matthias Groebel, Trusted Faces, 1995 / 2022

video loop, 2:41 min

(refurbished)

EN

The halftone dotted paint suggests that some kind of printing process was used, but it doesn’t look like screen print, more like plotter, or maybe a kind of inkjet? However, the works are dated 1990/91, so it wouldn’t add up chronologically – in the early 1990s there were no large-format color plotters yet.

Already at the time of their origin, the paintings raised questions about their technical feasibility when they were shown. Today, prints on canvas are common; the question How was it made? no longer comes up right away. But in the paintings at Schiefe Zähne, traces of a plotter avant la lettre can be seen, like the tip of an arrow of time pointing to a present that has now granted the wish for such a device after all. But then again, it's different from the one you can actually see at work on Matthias Groebel's website. Because, as he says, machines are never built for artists.

He himself had to invent the machinery he uses, and as with every invention, this meant putting together existing parts in a different way, contrary to their intended use, drawing on a wide range of scattered technical expertise. Programming the color application posed a particular challenge. When Matthias Groebel devised the machine, he didn’t want to approximate a realistic image by additive color mixing, the way four-color printing works. What he wanted instead was something like a painting device, a technical brush, allowing full control of the color space much in the same way as in painting, ultimately allowing him to work as he would in oil, from chiaroscuro gradients to creating an individual palette.

The use of machinery places the paintings in the realm of concrete art, specifically as, to summarize Wikipedia, creations of a direct sensory impression, which ideally can be described mathematically and be automated – detached from symbolic elements, with a focus on the interplay of form and color and an interest in the exploration of color.

However, this hermeticism, inherent in many works of concrete art, is actually seen as a flaw by Matthias Groebel, which he solved by selecting seemingly random images from television that remain open to interpretation. This is in keeping with concrete art, also with regard to the psychological or unmediated sensory experience of color space. But another psychological aspect is introduced as well, a kind of narrative that viewers are tempted to extrapolate from the stills that offer the possibility of recognizing / interpreting / attributing them. This is even more pronounced when the images are hung in series, practically asking to be strung together into a narrative (the Story of the Hand).

The color space – and that means Groebel's painterly choices – together with the plot, which defies a definitive conclusion, create the peculiar presence of these images. This is also thanks to a familiarity with the TV image, portrayed here in a kind of liquidity (the image of flow, derived from the moving image). This familiarity is met with the pictorial moment, that is, the punctum of the image. In this case, the moment Matthias Groebel chose from an endless stream of footage from early commercial television imagery, a moment which intrigued him to such an extent that he reassembled it, actually reconstructed it, with the help of his machine.

And so, while the technical process of Matthias Groebel's paintings has been realized or normalized into the present, their content or subject has vanished into the past. Even though they are now 30 years old, this renders the works extremely topical, perhaps precisely because two arrows of time intersect in them, one pointing to the future, the other pointing to the past. Where these two cross is in fact: Now (albeit in a fluid way).

– Ariane Müller

DE

Punktförmige Rasterungen im Farbauftrag – das weist auf ein Druckverfahren hin, sieht jedoch nicht aus wie Siebdruck, eher wie Plotter, eine Art Tintenstrahldruck? Die Datierung der Bilder, 1990/91, jedoch – das kommt zeitlich nicht hin – Anfang der 1990er Jahre gab es noch keine großformatigen Farbplotter.

Zum Zeitpunkt ihrer Entstehung warfen die Bilder denn auch, wenn ausgestellt, vor allem Fragen nach ihrer technischen Machbarkeit auf. Heute ist man Farbdruckverfahren auf Leinwand gewöhnt; die Frage, Wie ist das gemacht? stellt sich nicht mehr unmittelbar. In den Bildern in der Galerie Schiefe Zähne sieht man aber einen Plotter avant la lettre, wie die Spitze eines Zeitpfeils in eine Gegenwart, die den Wunsch nach diesem Drucker nun doch noch erfüllt hat. Obwohl dann doch auch wieder anders als dieser, dem man auf Matthias Groebels Website bei der Arbeit zusehen kann. Denn, wie er sagt: Maschinen wurden noch nie für Künstler gebaut.

Seine Maschine musste er damals soweit selbst erfinden und wie bei jeder Erfindung hieß das, Bestehendes anders zusammenzufügen, gegen den eigentlichen Gebrauch der einzelnen Teile und mit Hilfe verschiedenster, verstreuter technischer Expertise. Eine Schwierigkeit war dabei die Programmierung des Farbauftrags, denn in der Konzeption der Maschine wollte Matthias Groebel nicht die Annäherung an ein realistisches Bild durch additive Farbmischung, wie das der Vierfarbdruck macht, sondern so etwas wie ein Malgerät, einen technischen Pinsel, mit der Möglichkeit, den Farbraum wie beim Malen steuern zu können, und damit letztlich wie in der Ölmalerei vorgehen zu können, von der Hell-Dunkel-Verteilung hinein in eine individuelle Palette.

Die Beschäftigung mit Malmaschinen weist die Bilder in das Feld der konkreten Kunst – also der: Erzeugung eines direkten sinnlichen Eindrucks, im Idealfall mathematisch beschreibbar, automatisierbar – abseits von symbolischen Bildelementen mit Konzentration auf das Zusammenspiel von Form und Farbe und einem Interesse an der Erforschung der Farbe (als Zusammenfassung aus Wikipedia).

Die Hermetik, die allerdings vielen Arbeiten dieses Feldes anhaftet und die Matthias Groebel eigentlich als Problem sieht, löst er durch ein aus dem Fernsehen genommenes Bild, das randomisiert, aber dennoch bedeutungsoffen ist. Das bewegt sich weiterhin innerhalb des Feldes des Konkreten – auch in Hinblick auf den psychologisch/unmittelbar sinnlich erfahrbaren Farbraum –, insertiert da aber etwas weiteres Psychologisches, nämlich eine Art Erzählung, die die Betrachtenden aus dem Bild machen wollen, indem es ihnen die Möglichkeit gibt, es zu erkennen/zu deuten/zu bedeuten. Noch stärker sichtbar wird das, wenn die Bilder als Serien gehängt werden und nahezu dazu auffordern, wieder zu einer Erzählung zusammengefügt zu werden (die Geschichte der Hand).

Der Farbraum – und das heißt Groebels malerische Entscheidung – zusammen mit der nicht endgültig zu Ende erzählbaren Handlung, erzeugen denn auch die eigenartige Präsenz dieser Bilder. Diese ist auch Vertrautheit mit dem Fernsehbild, das hier malerisch auch in einer Art Liquidität (das Fließband, denn es kommt ja aus dem Bewegtbild) nacherzählt wird. Diese Vertrautheit trifft sich mit dem Bild-Moment, also dem Punktum des Bildes, in diesem Fall der Moment, den Matthias Groebel gewählt hat, aus einer endlosen Reihe an Footage aus den frühen Privatfernsehbildern, der ihn soweit interessiert hat, dass er ihn mit Hilfe der Maschine wieder zusammengesetzt, eigentlich rekonstruiert hat.

Während sich also das technische Verfahren, in dem Matthias Groebels Bilder entstanden sind, in die Gegenwart realisiert oder normalisiert hat, ist ihr Inhalt oder ihr Sujet in die Vergangenheit verschwunden. Das macht sie, obwohl sie nun 30 Jahre alt sind, extrem heutig, und vielleicht eben gerade deshalb, weil sich in ihnen zwei Zeitpfeile kreuzen, einer, der in die Zukunft und einer, der in die Vergangenheit weist.

Da, wo sich diese beiden kreuzen, ist eben: Jetzt (wenn auch fließend).

– Ariane Müller