Mathis Gasser

Heroes and Ghosts

September 16 – November 25, 2022

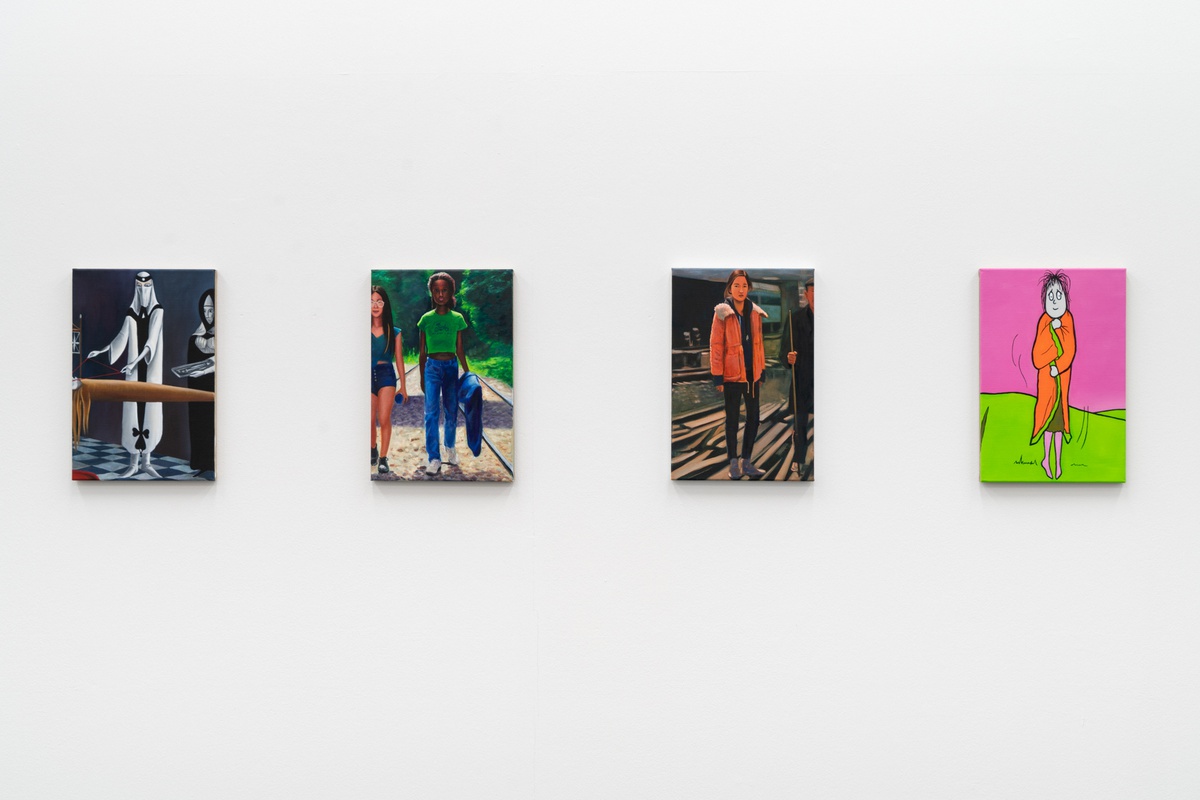

Mathis Gasser, Nami Matsushima 2, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Mathis Gasser, Ada, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

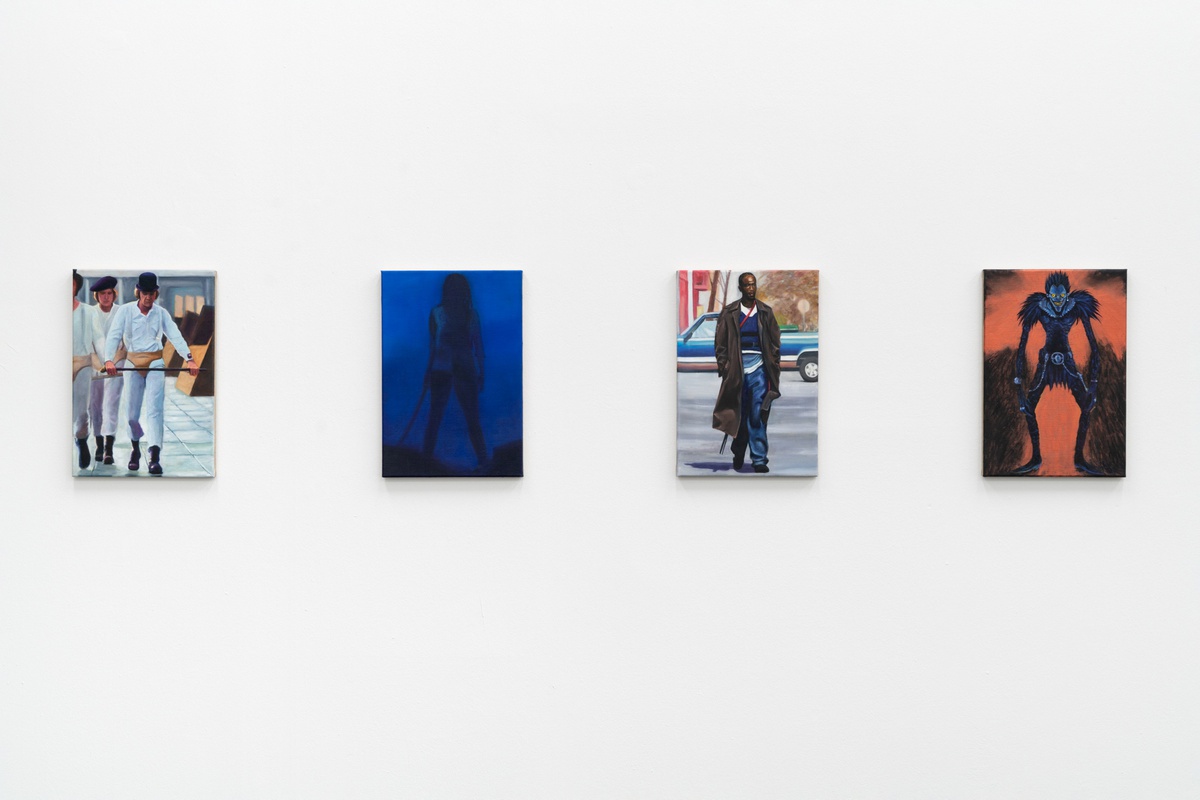

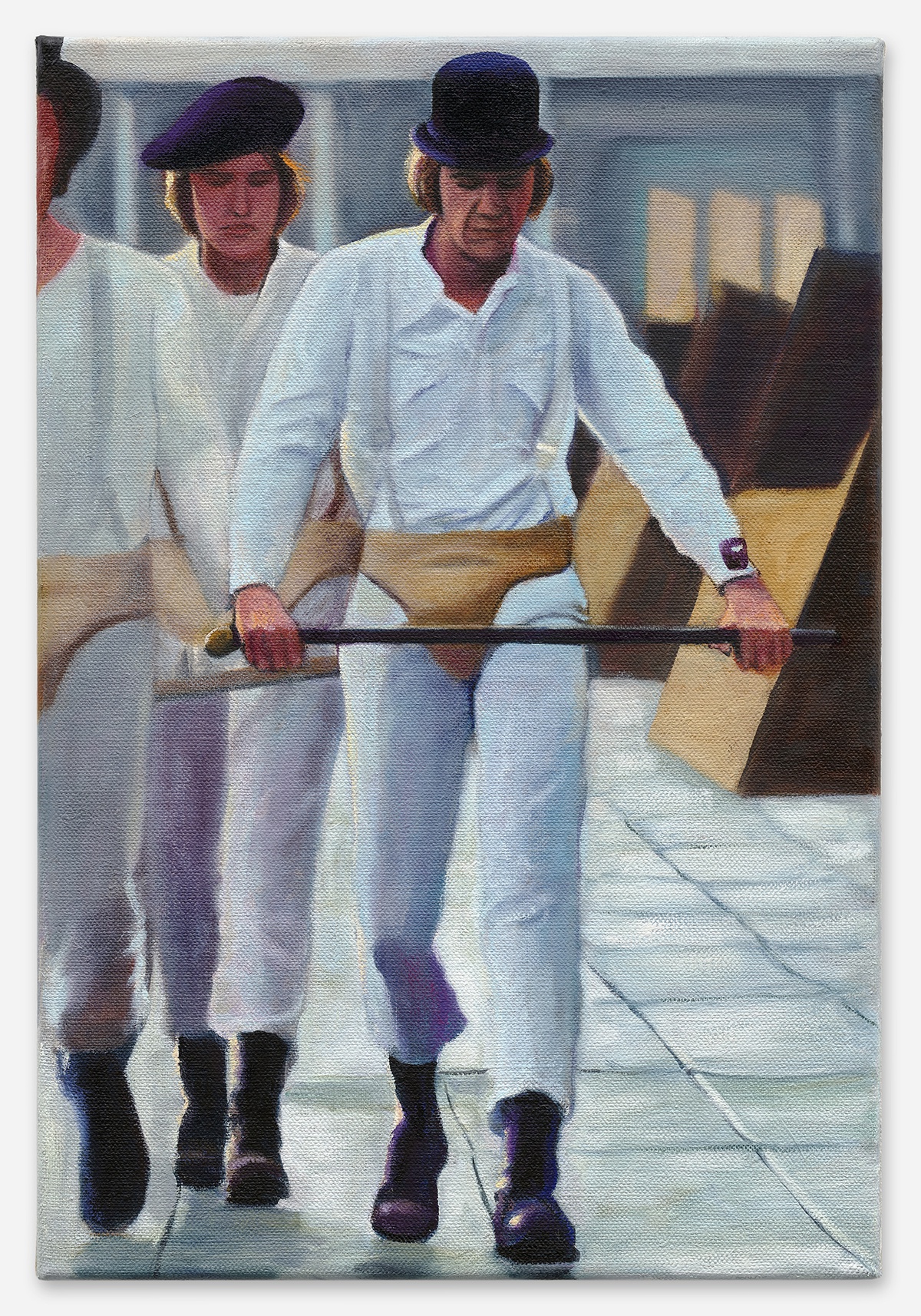

Mathis Gasser, Alex DeLarge, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

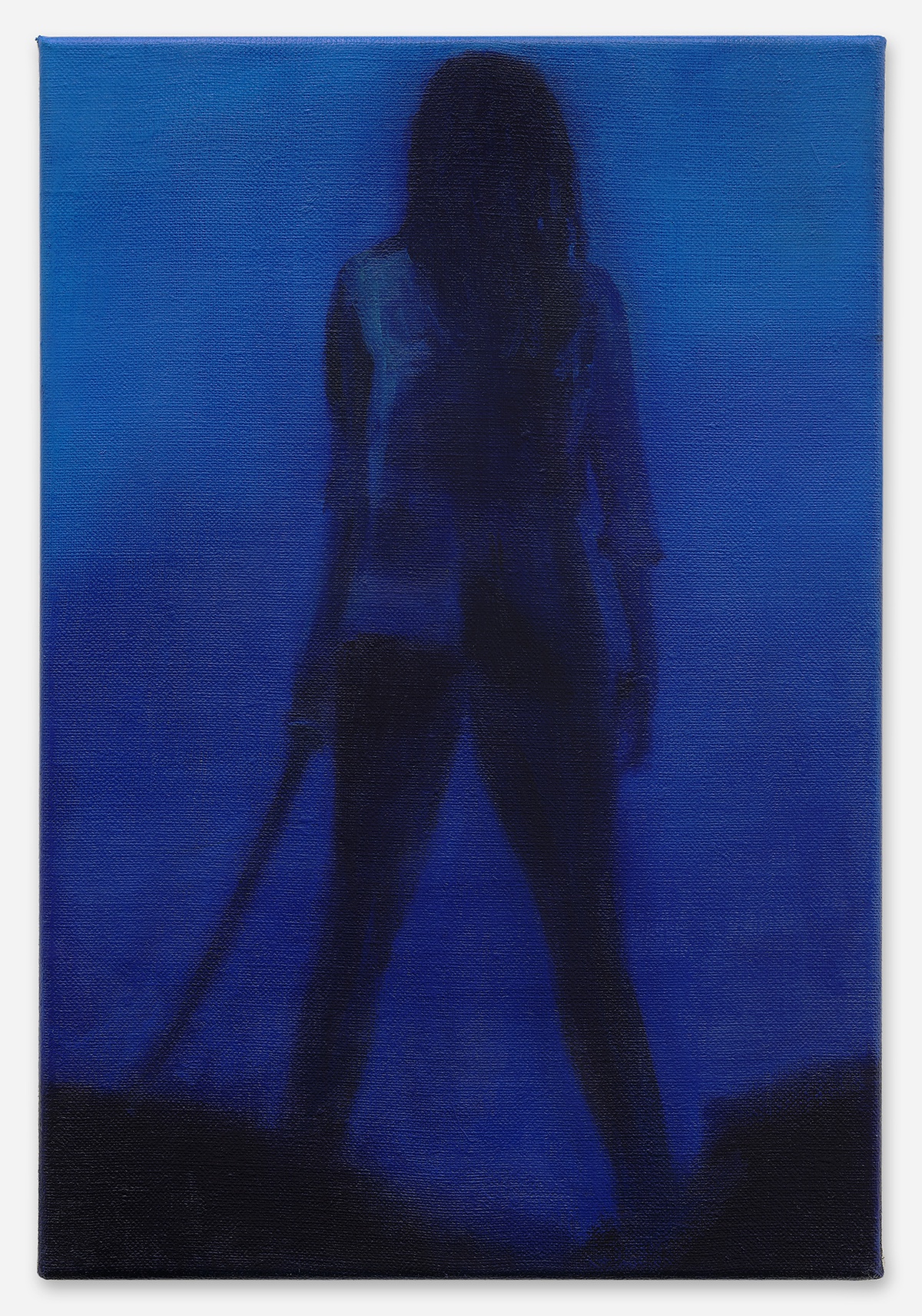

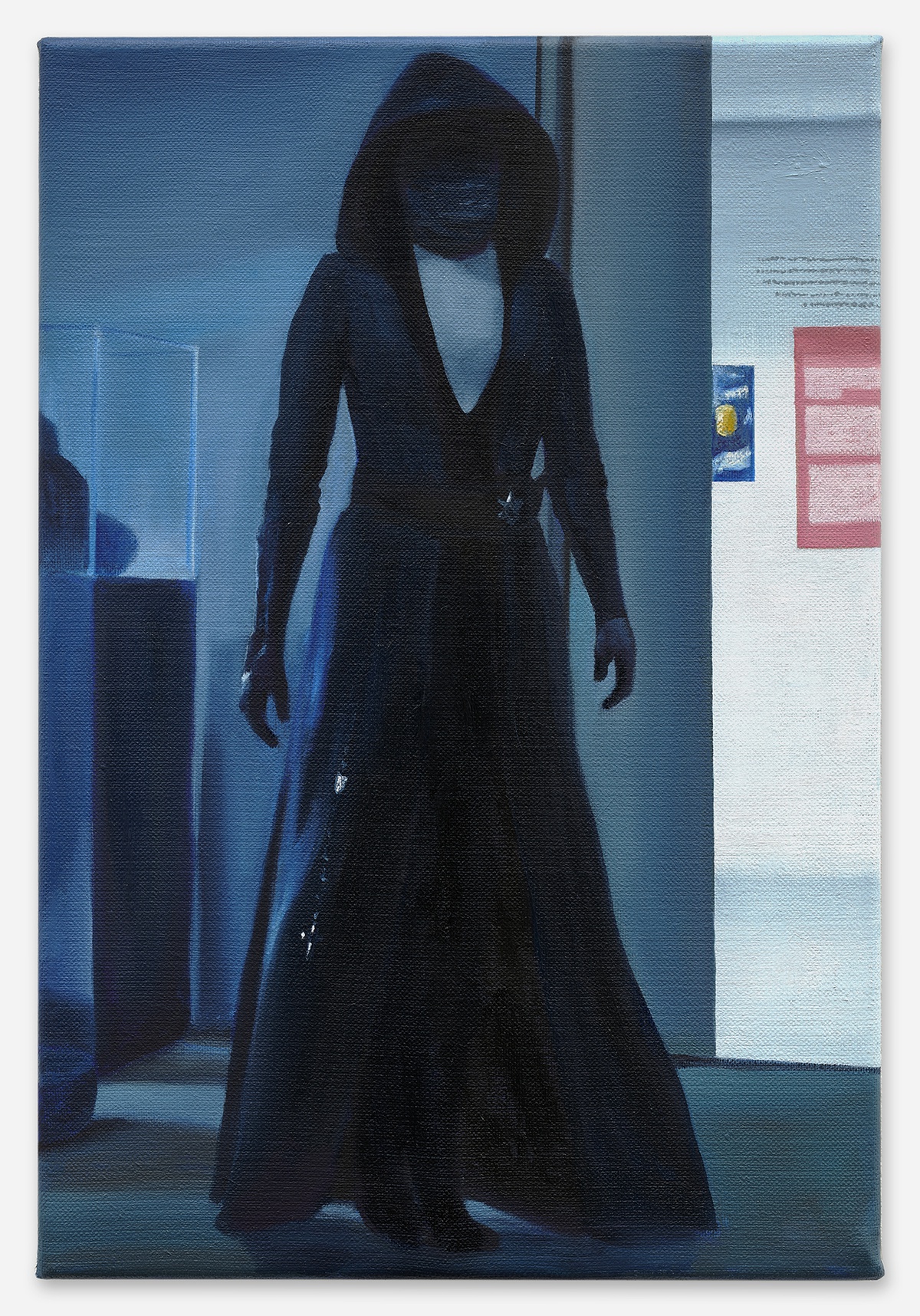

Mathis Gasser, Michonne 2, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

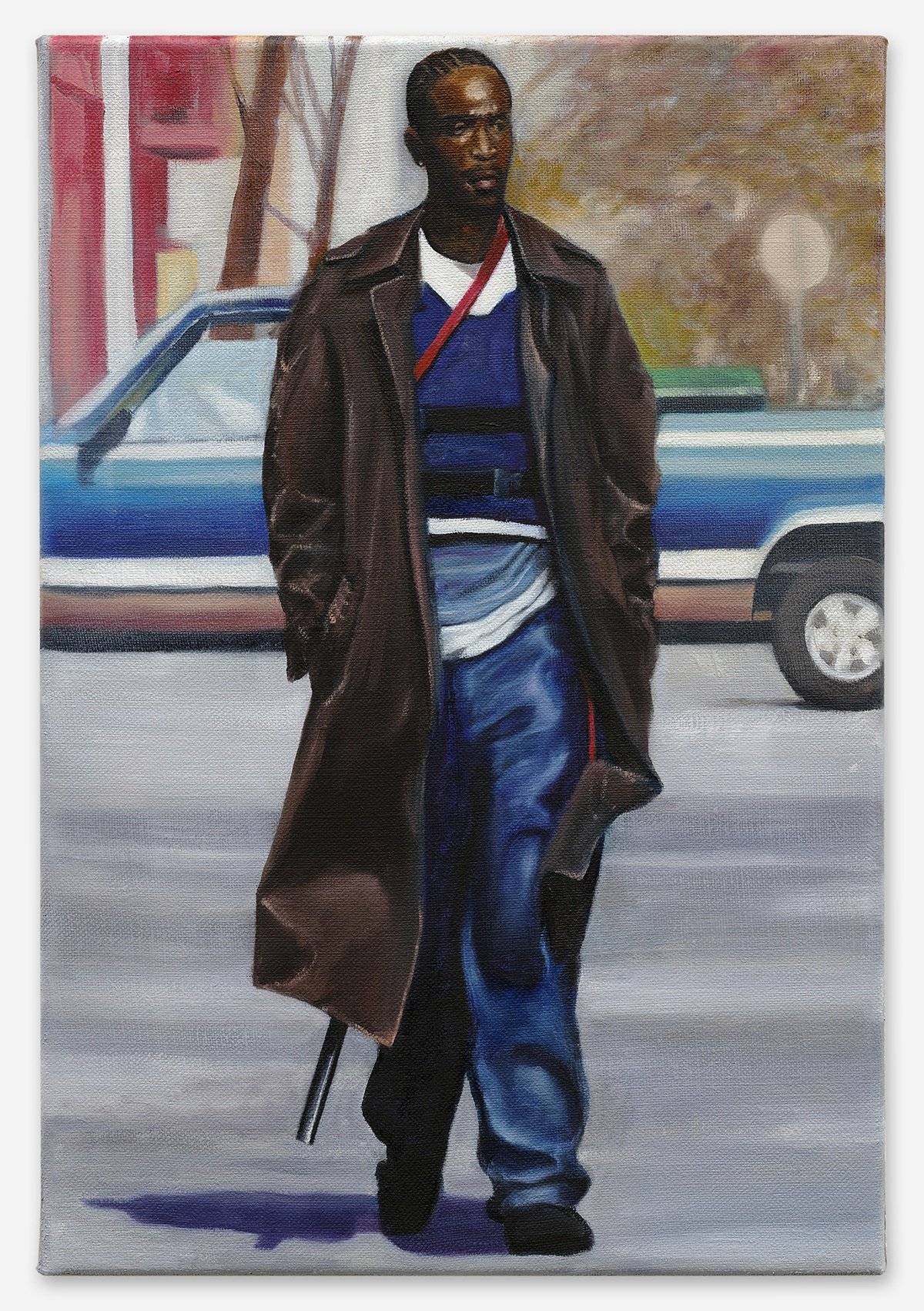

Mathis Gasser, Omar Little 3, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Mathis Gasser, Ryuk, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

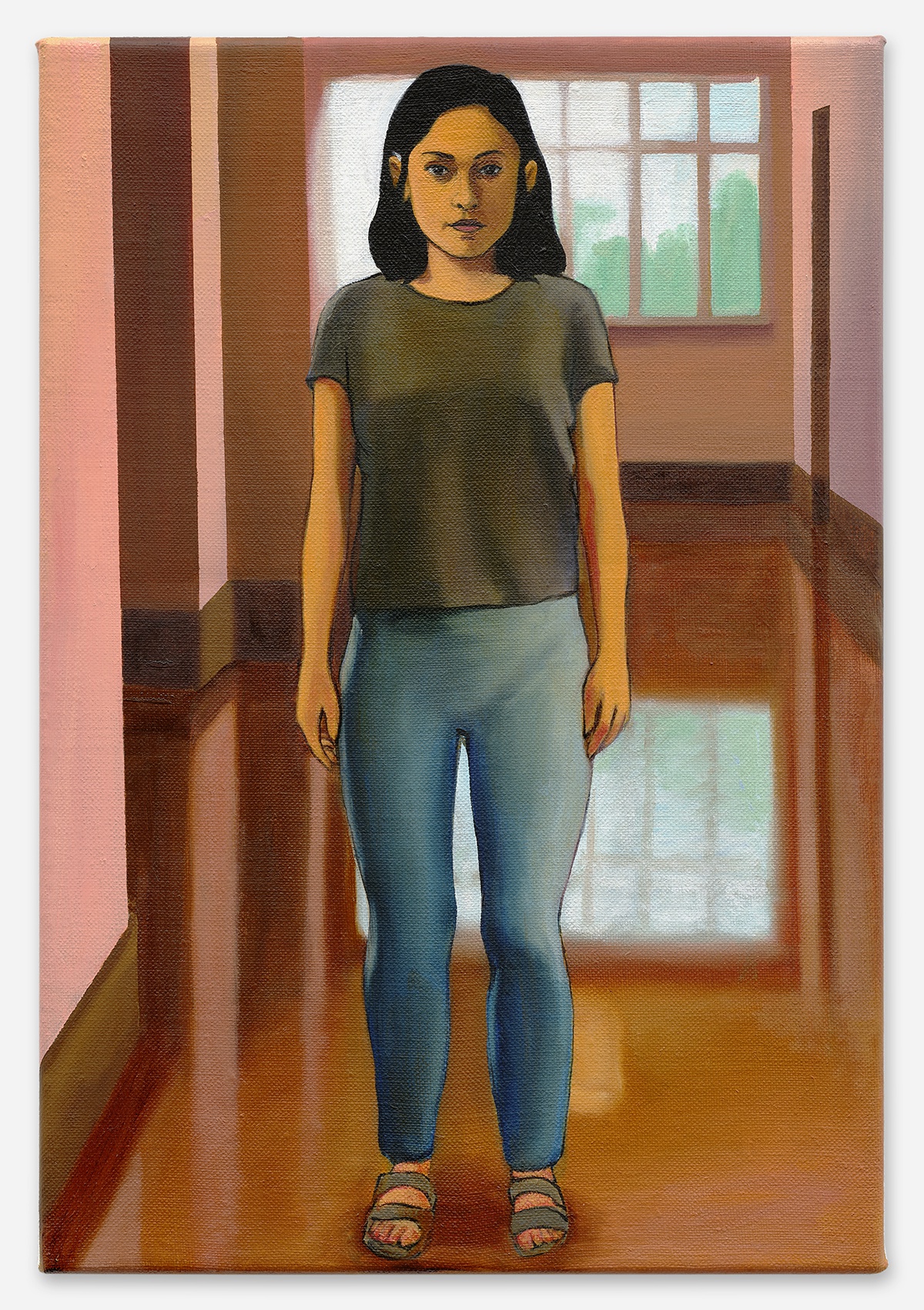

Mathis Gasser, Bernadine Williams, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Mathis Gasser, Alma Winograd-Diaz, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Mathis Gasser, Maeve Millay 2, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

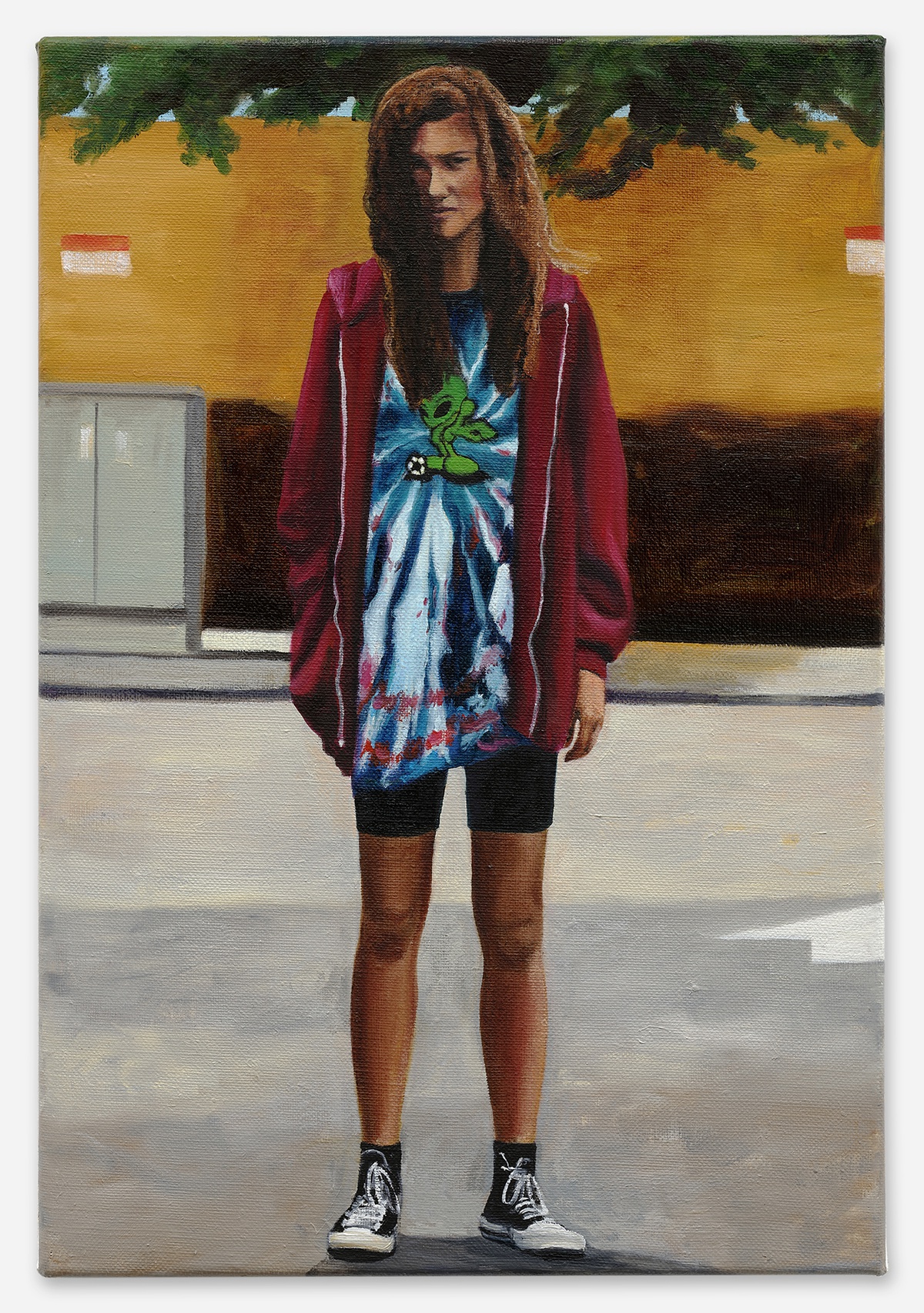

Mathis Gasser, Rue Bennett, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

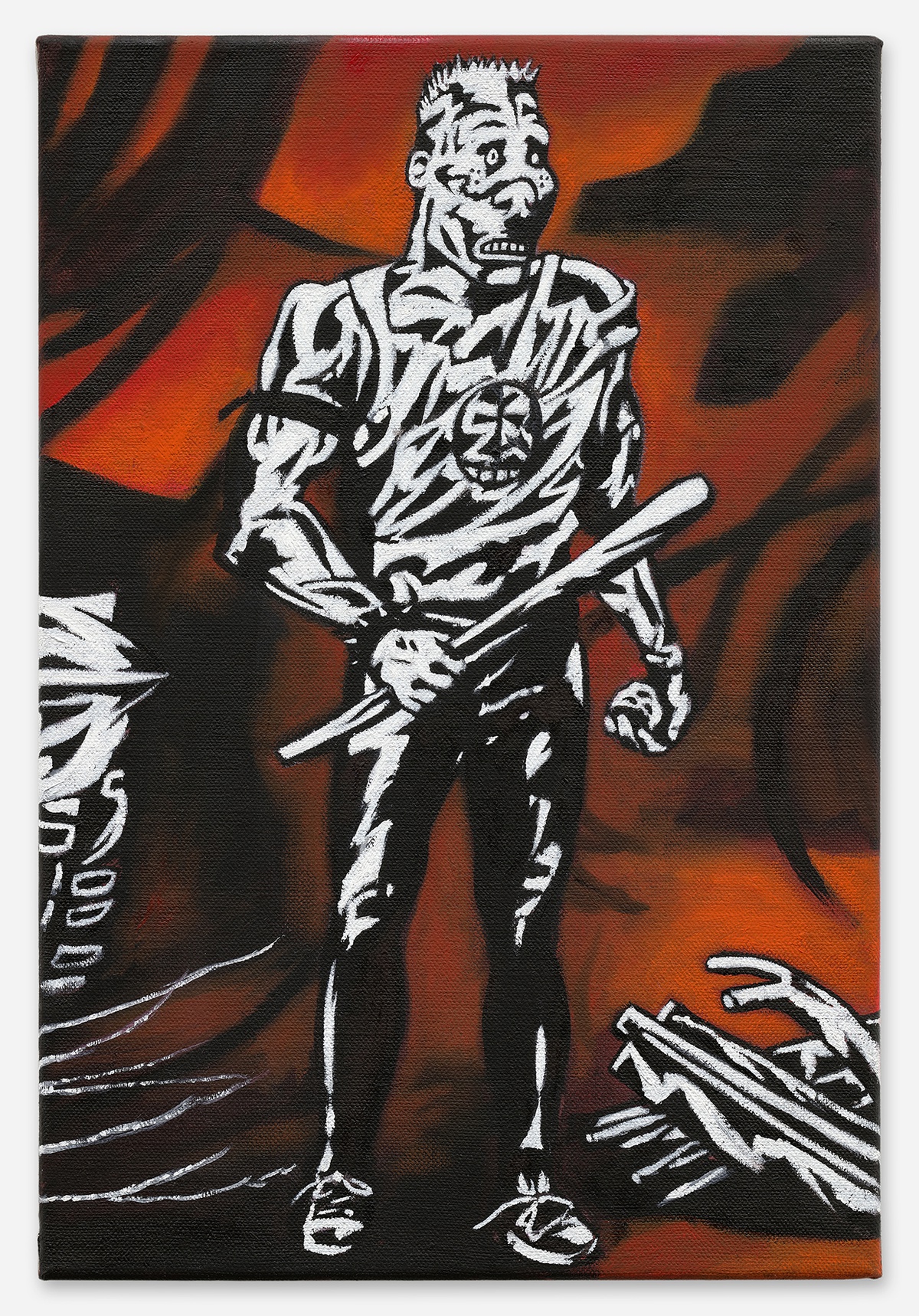

Mathis Gasser, Jiimbo (After Gary Panter), 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

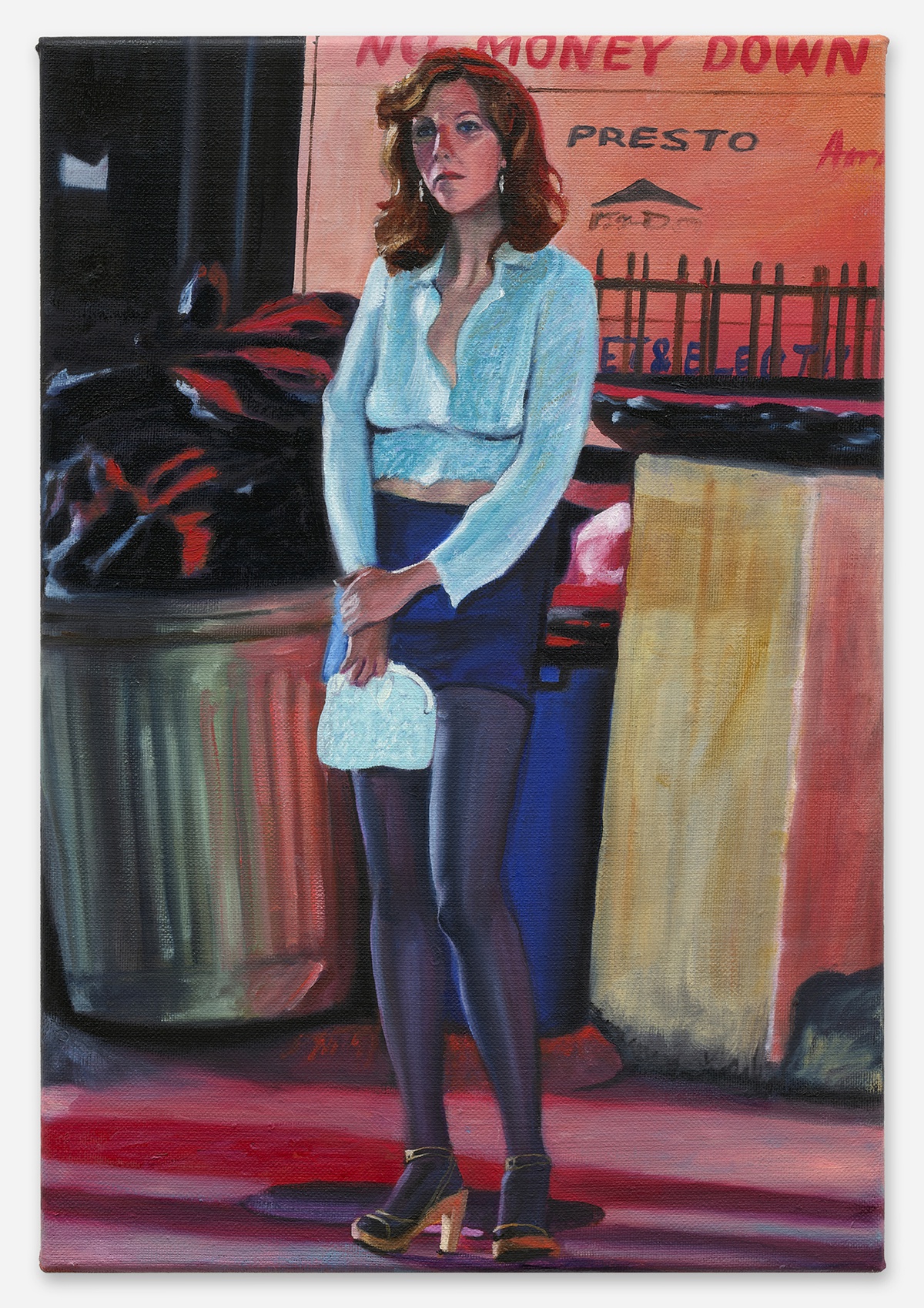

Mathis Gasser, Eileen "Candy" Merrell, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

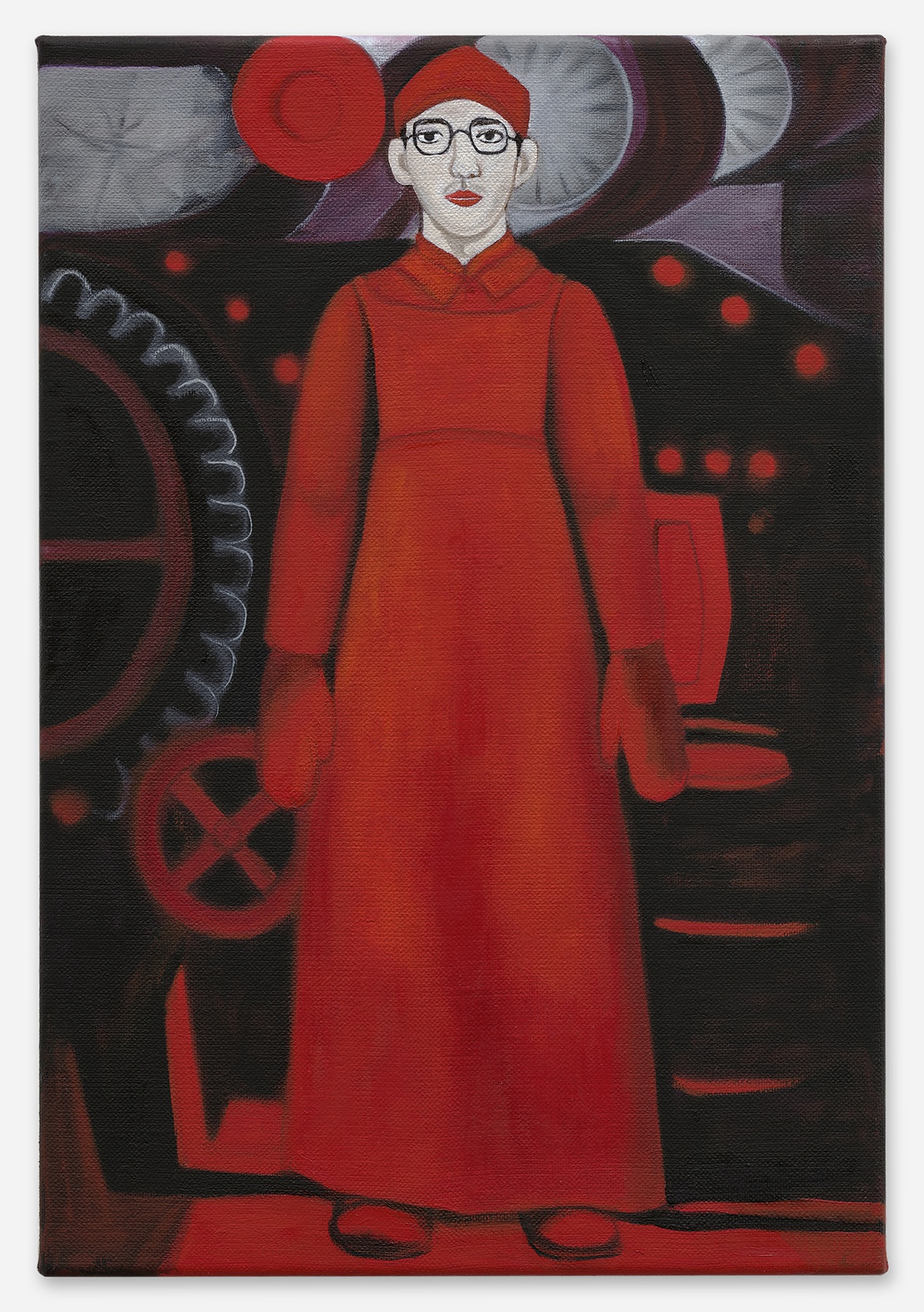

Mathis Gasser, Grosser roter Fabrikarbeiter (After Rudolf Maeglin), 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

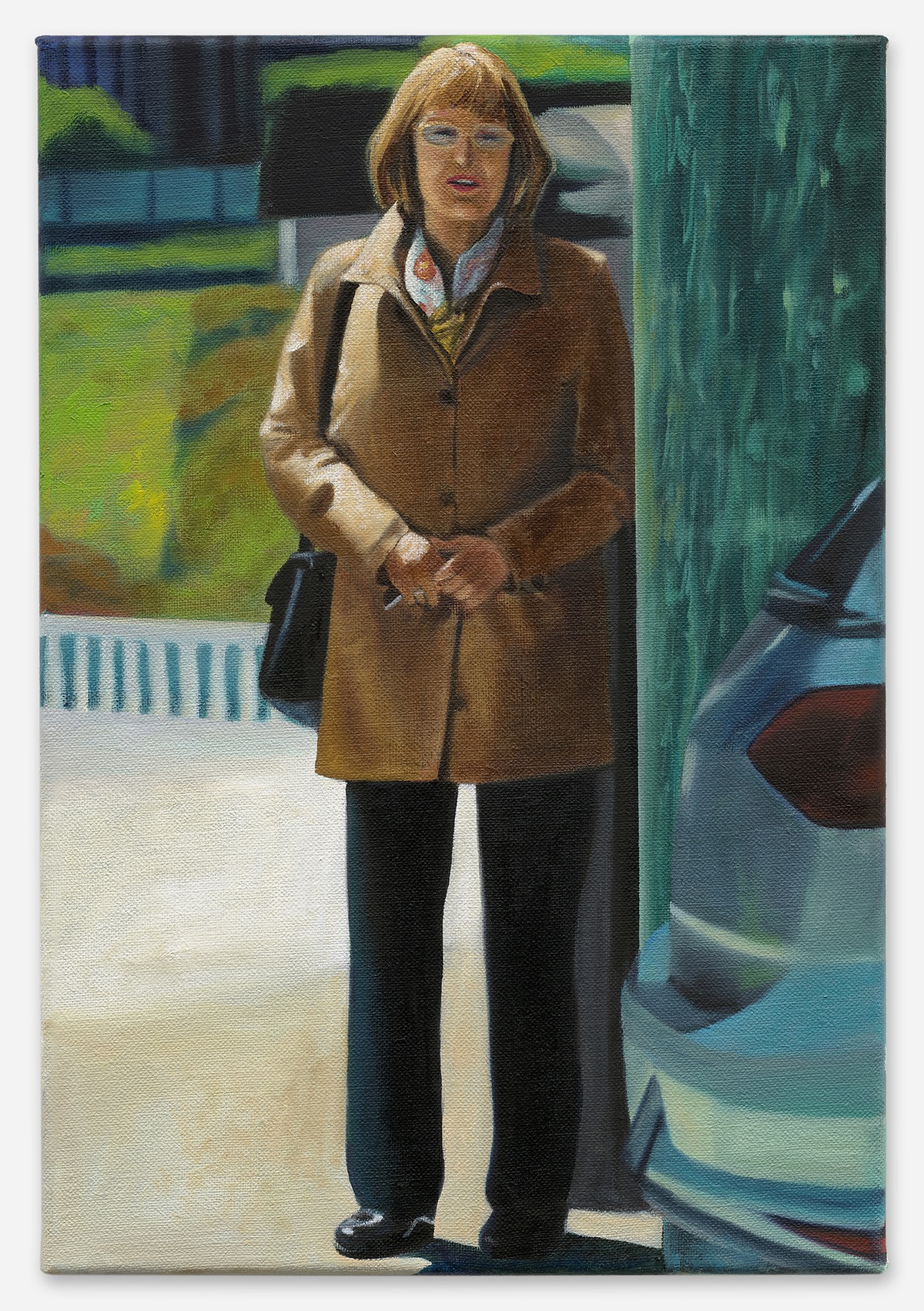

Mathis Gasser, Mary Louise Wright, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

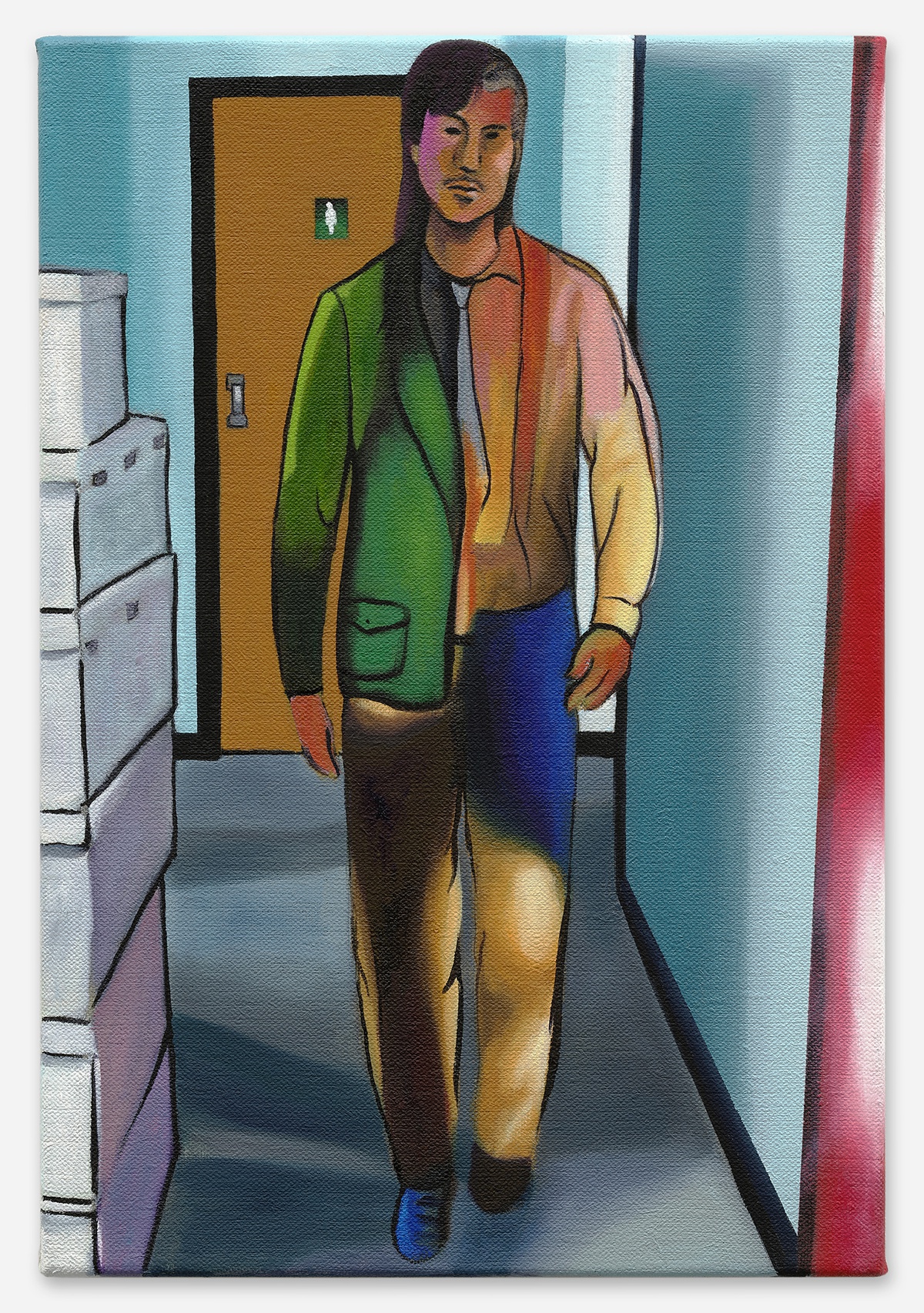

Mathis Gasser, Bob Arctor, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

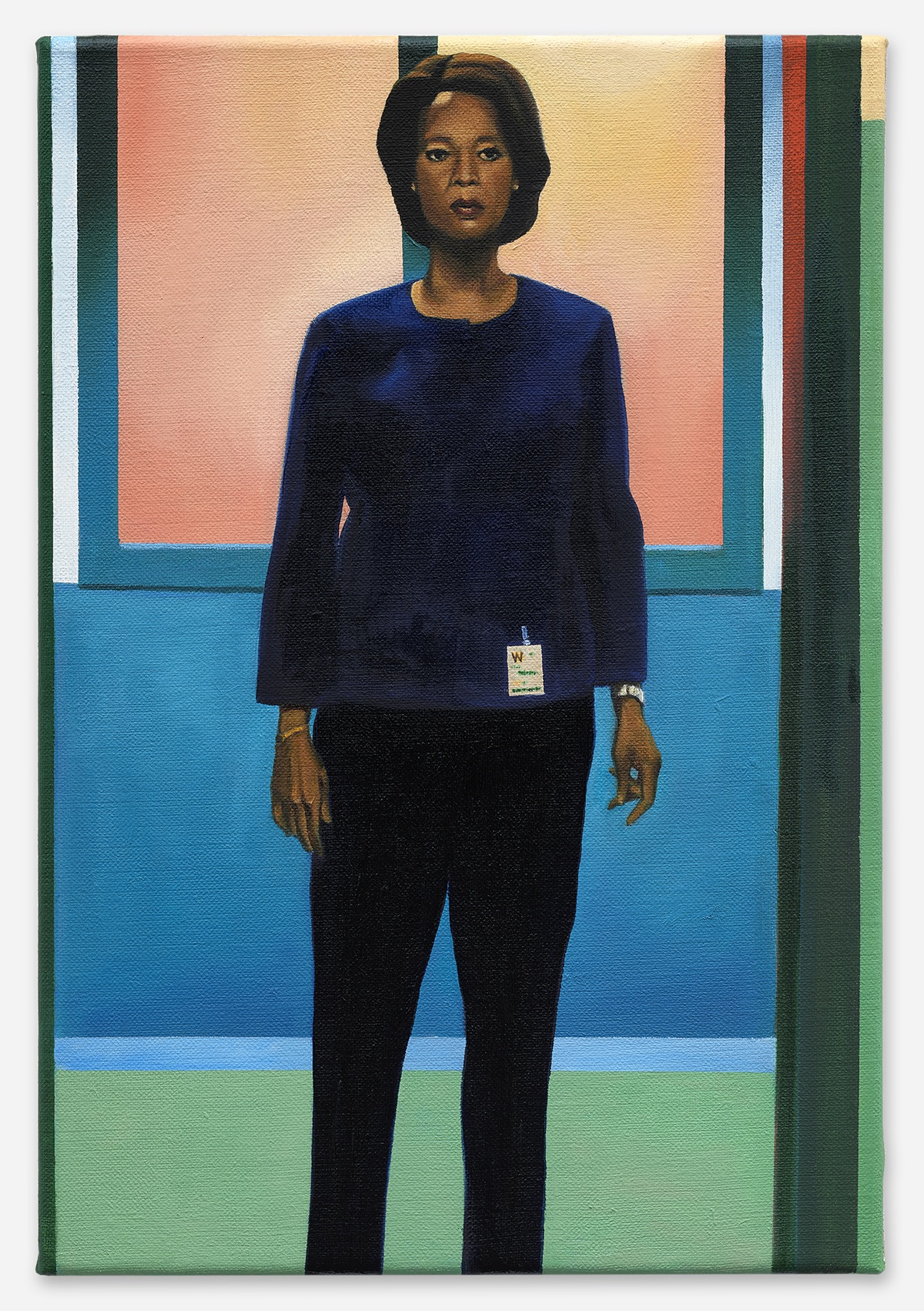

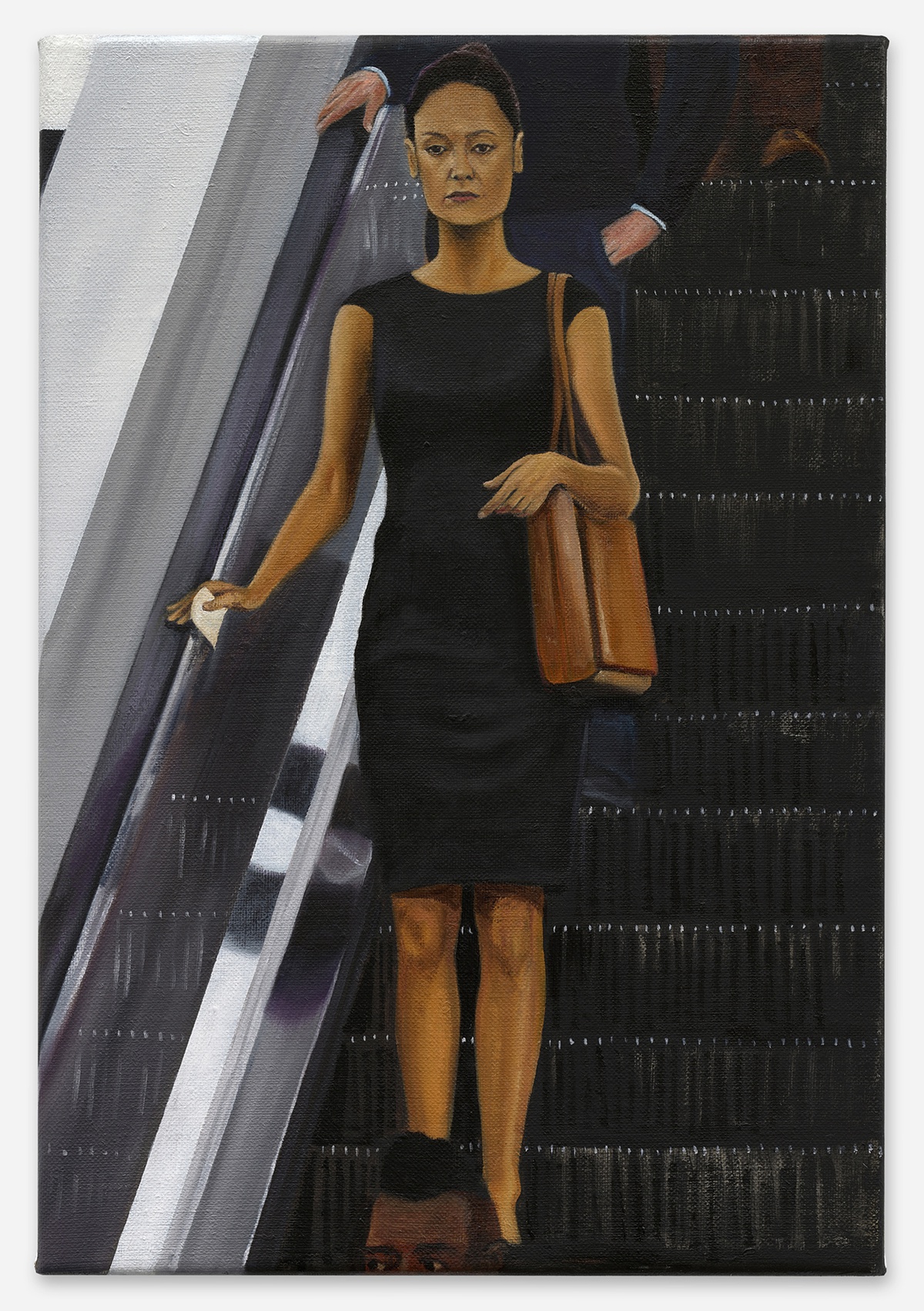

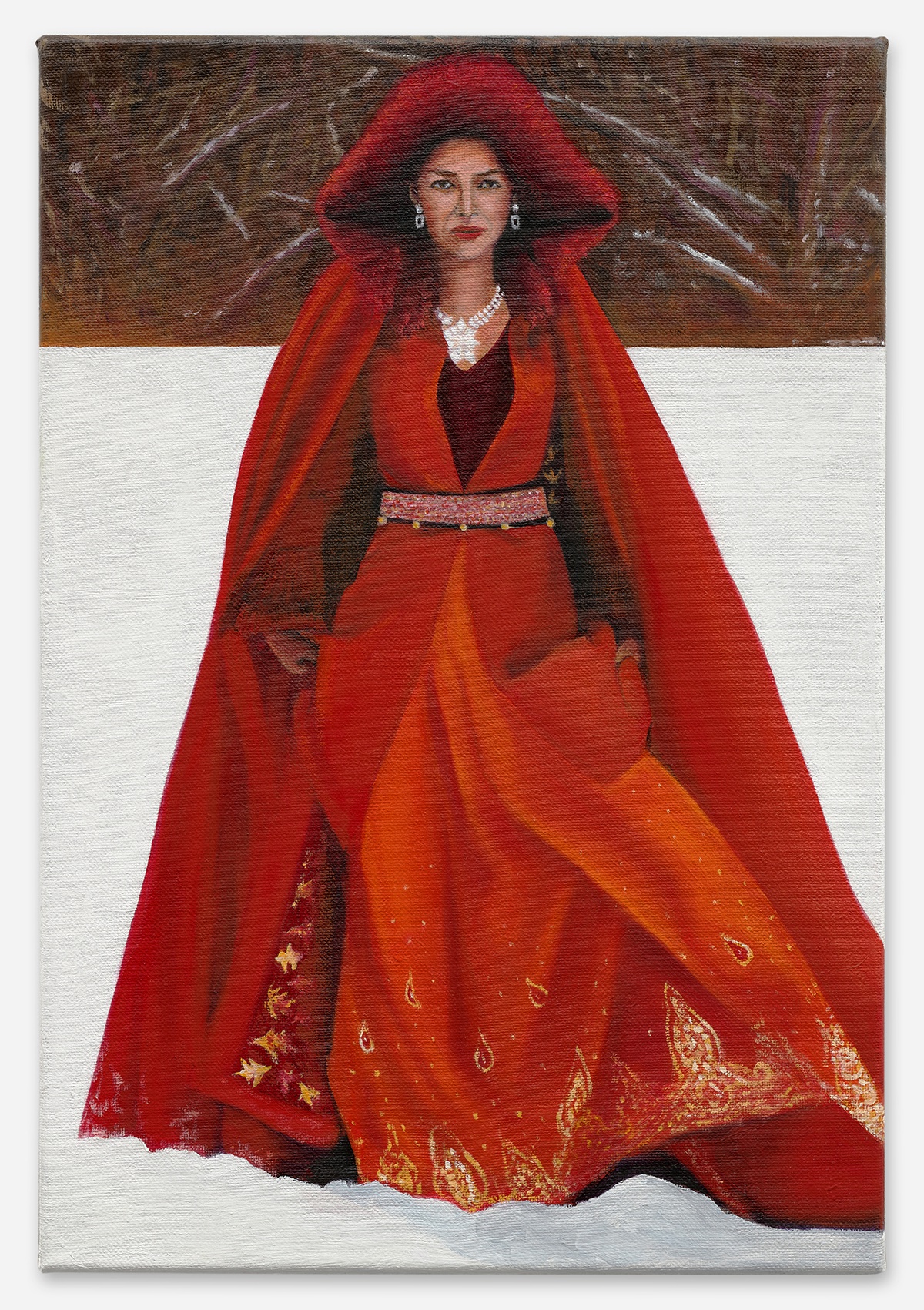

Mathis Gasser, Chrisjen Avasarala, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

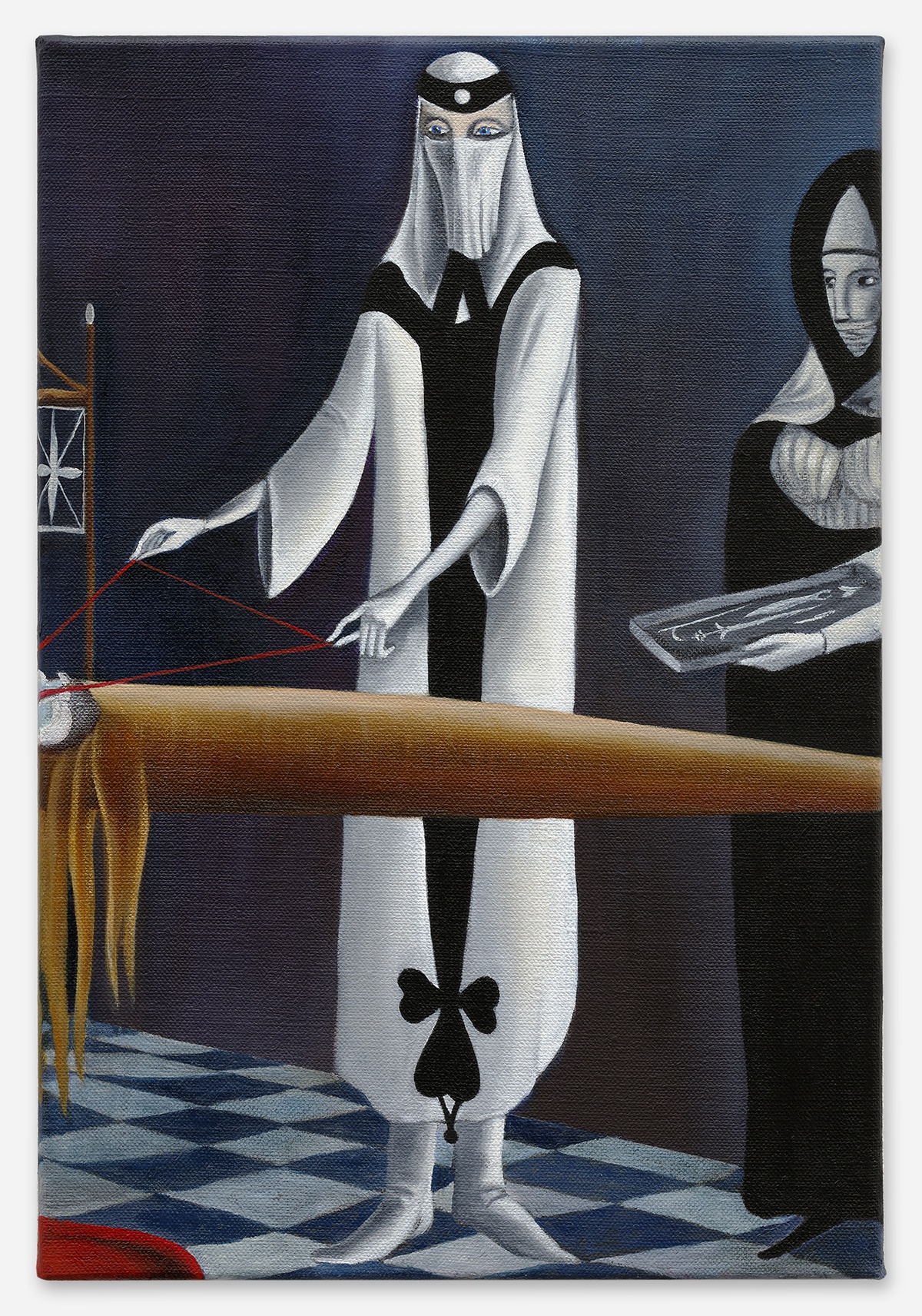

Mathis Gasser, Adieu Amenothep (After Leonora Carrington), 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

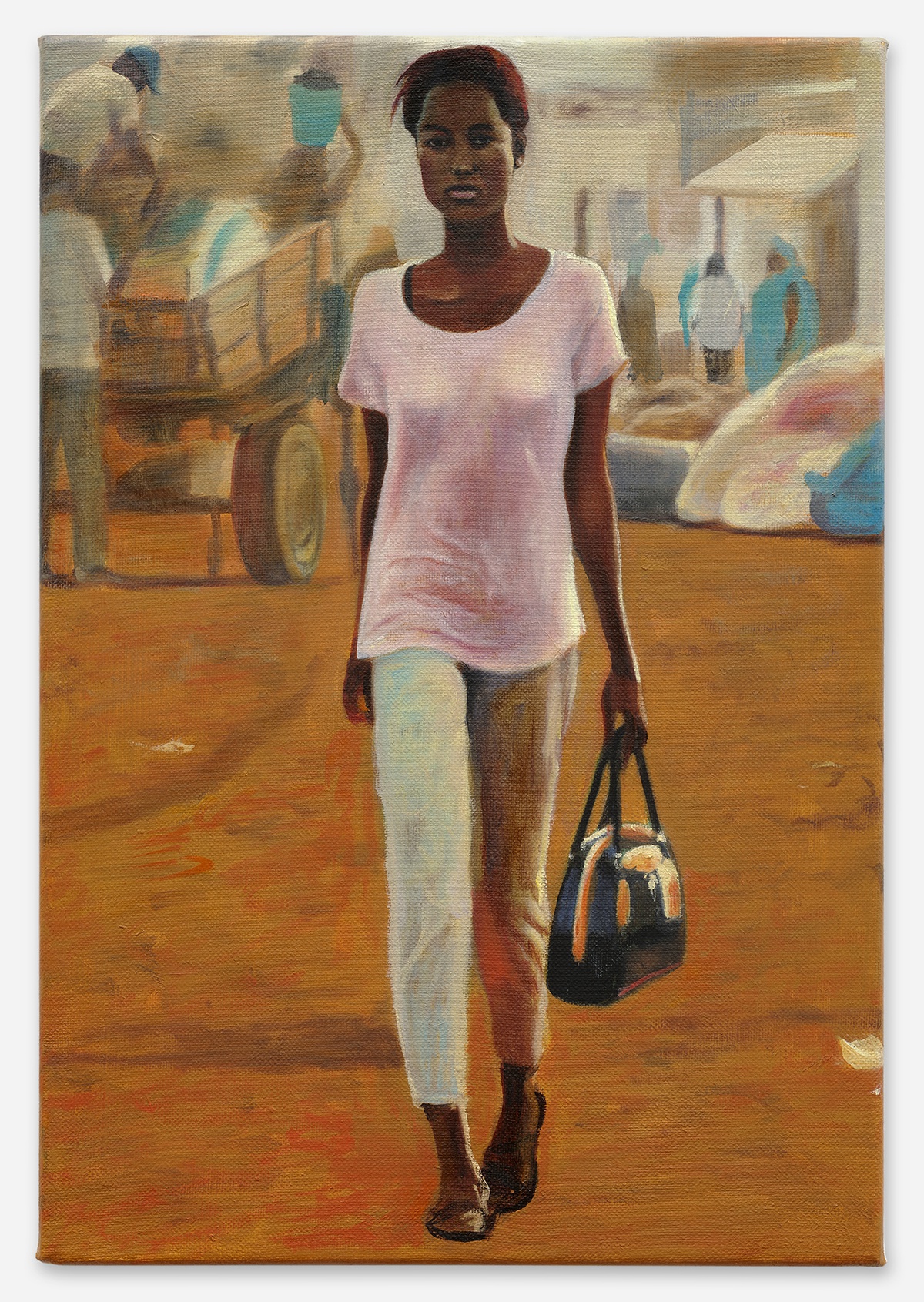

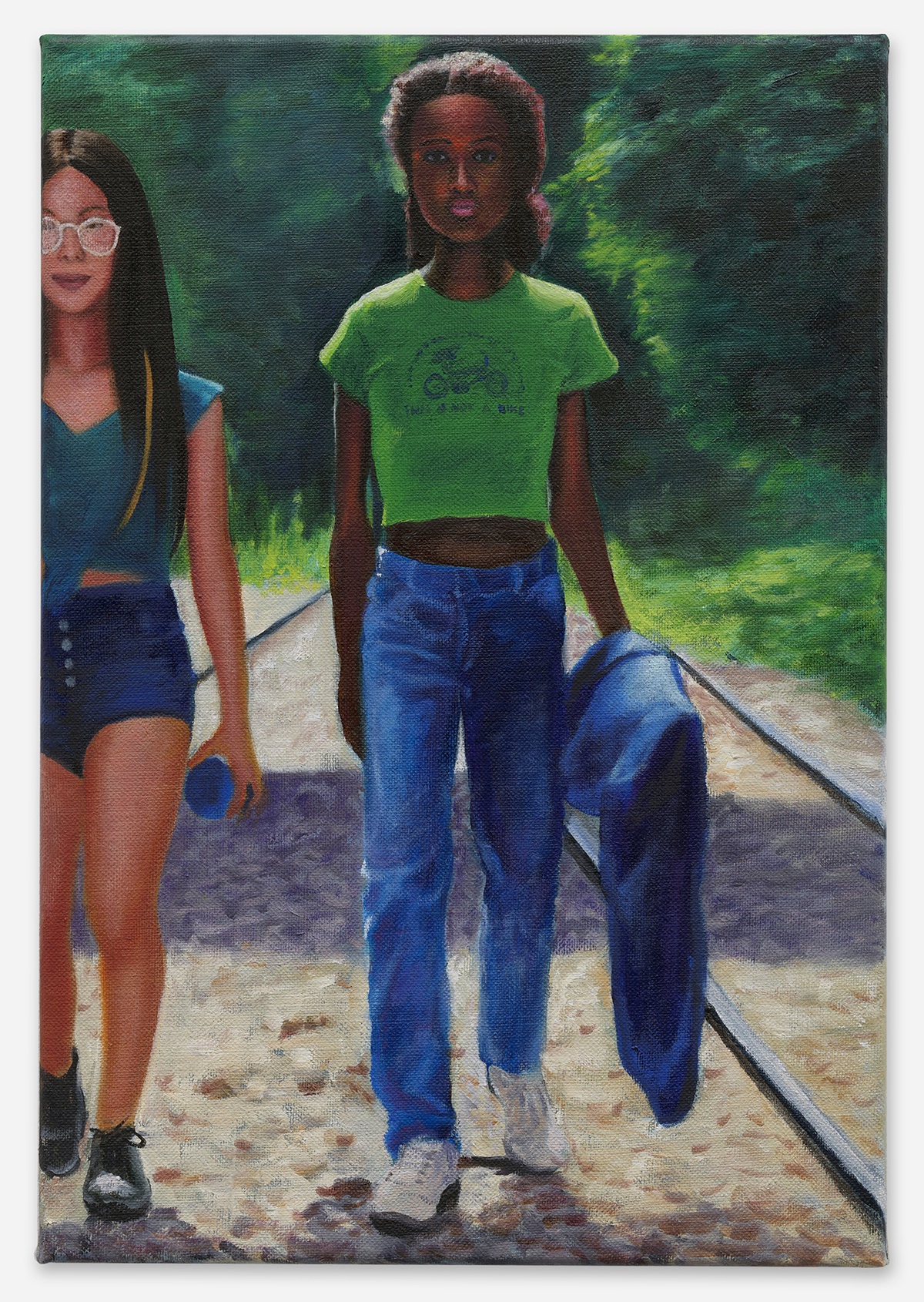

Mathis Gasser, Aminata "Amy" Diop, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

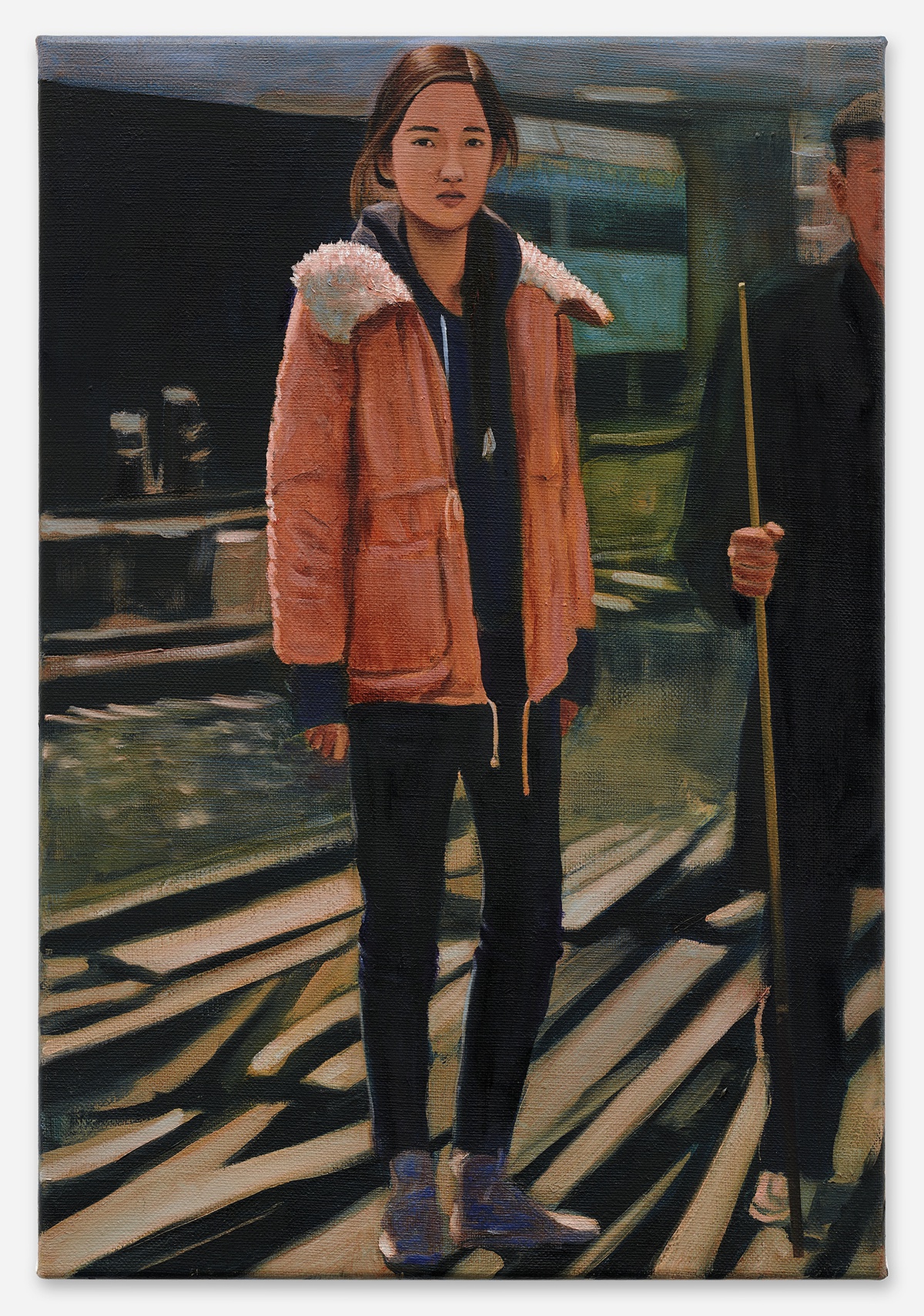

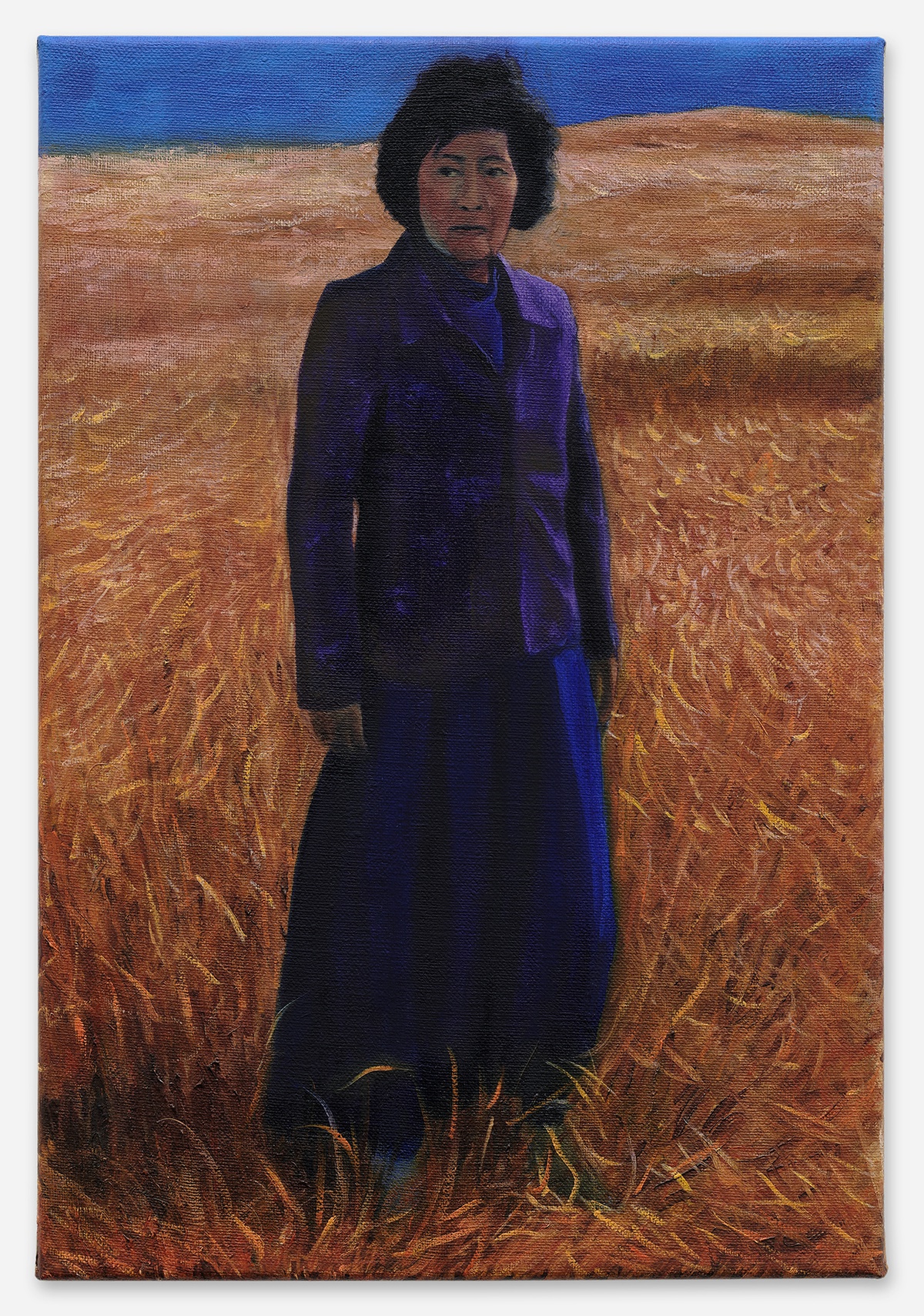

Mathis Gasser, Huang Ling, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Mathis Gasser, Y Llipryn Llwyd (After Angharad Tomos), 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

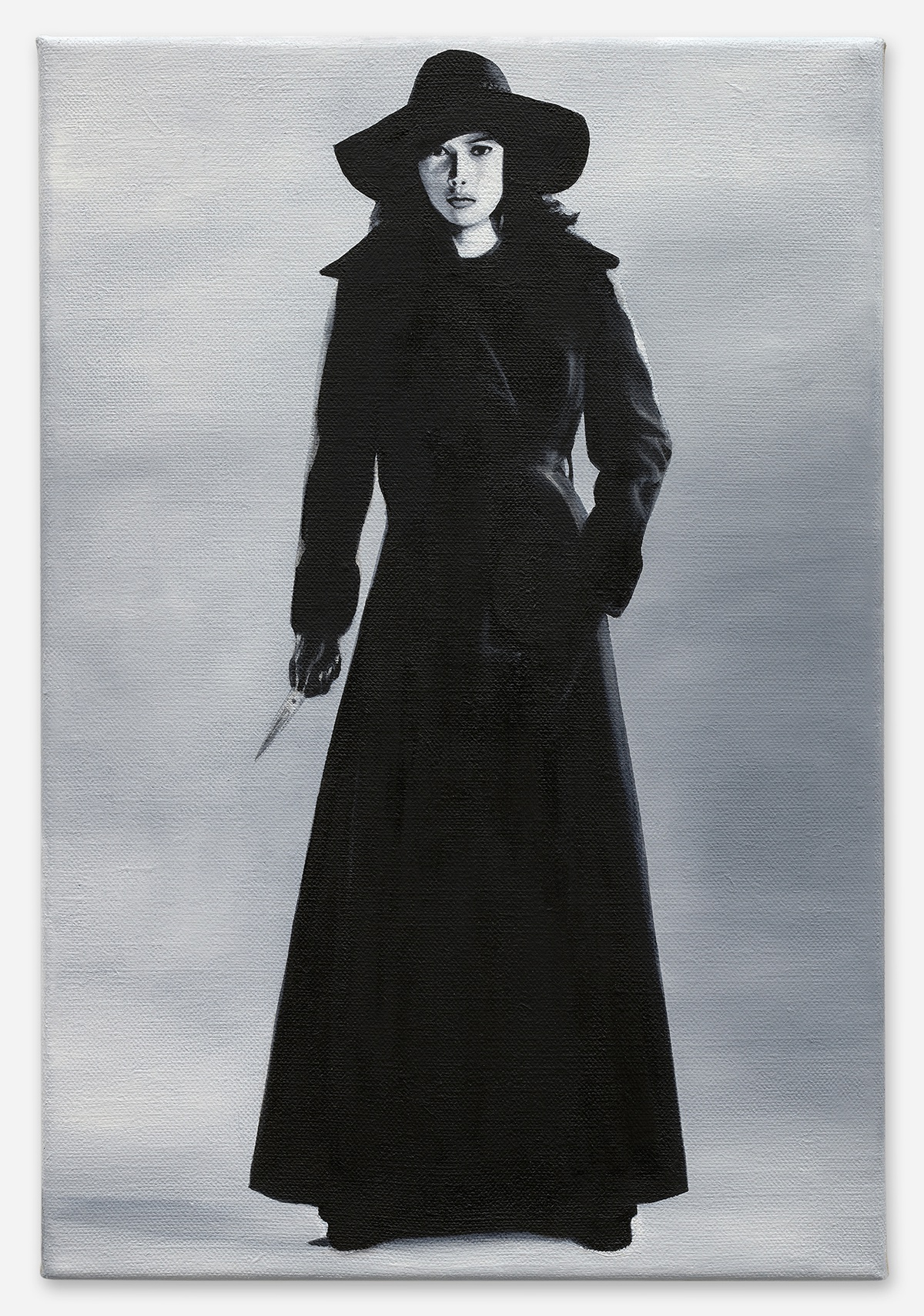

Mathis Gasser, Angela Abar, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Mathis Gasser, Mother, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

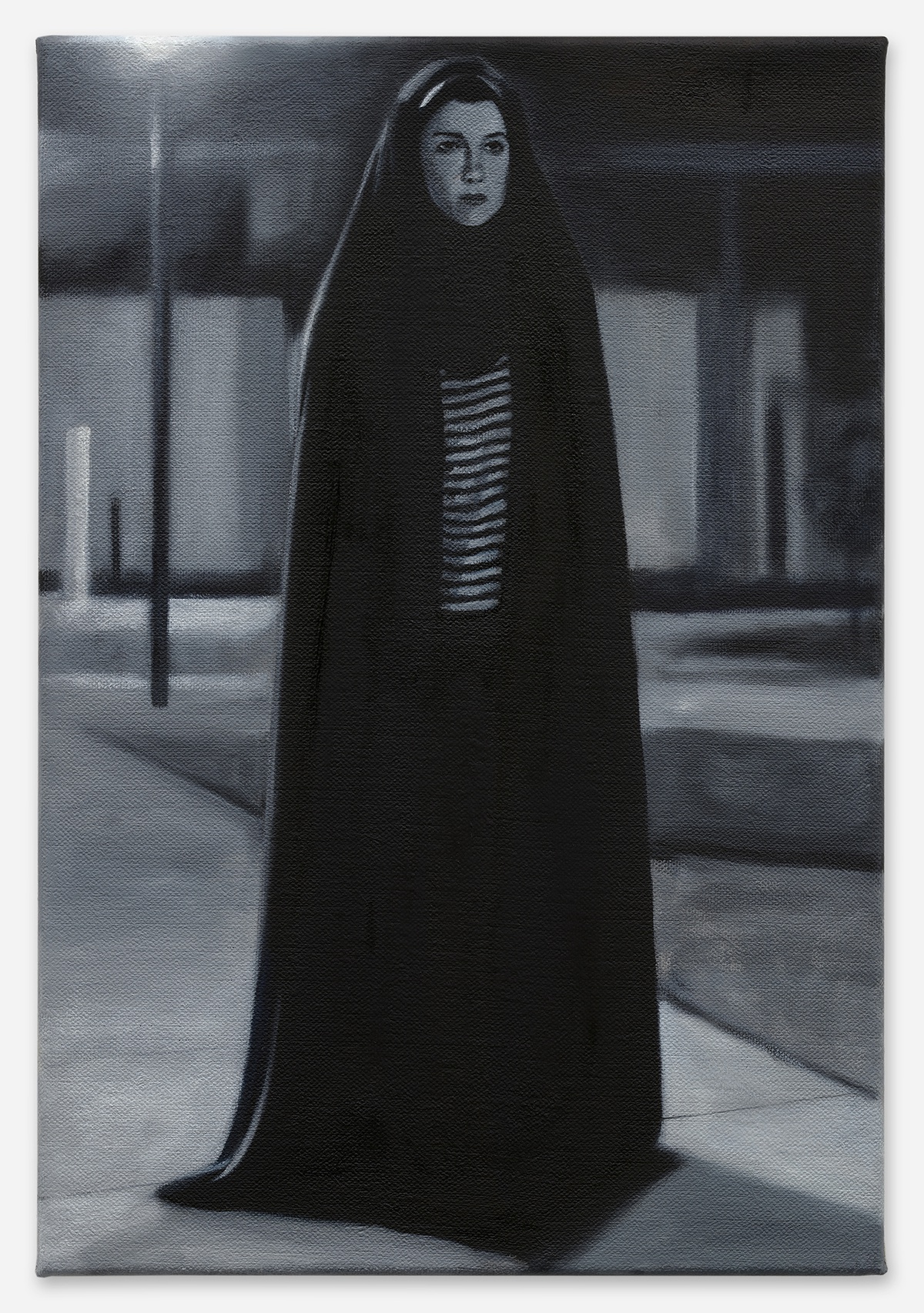

Mathis Gasser, The Girl, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

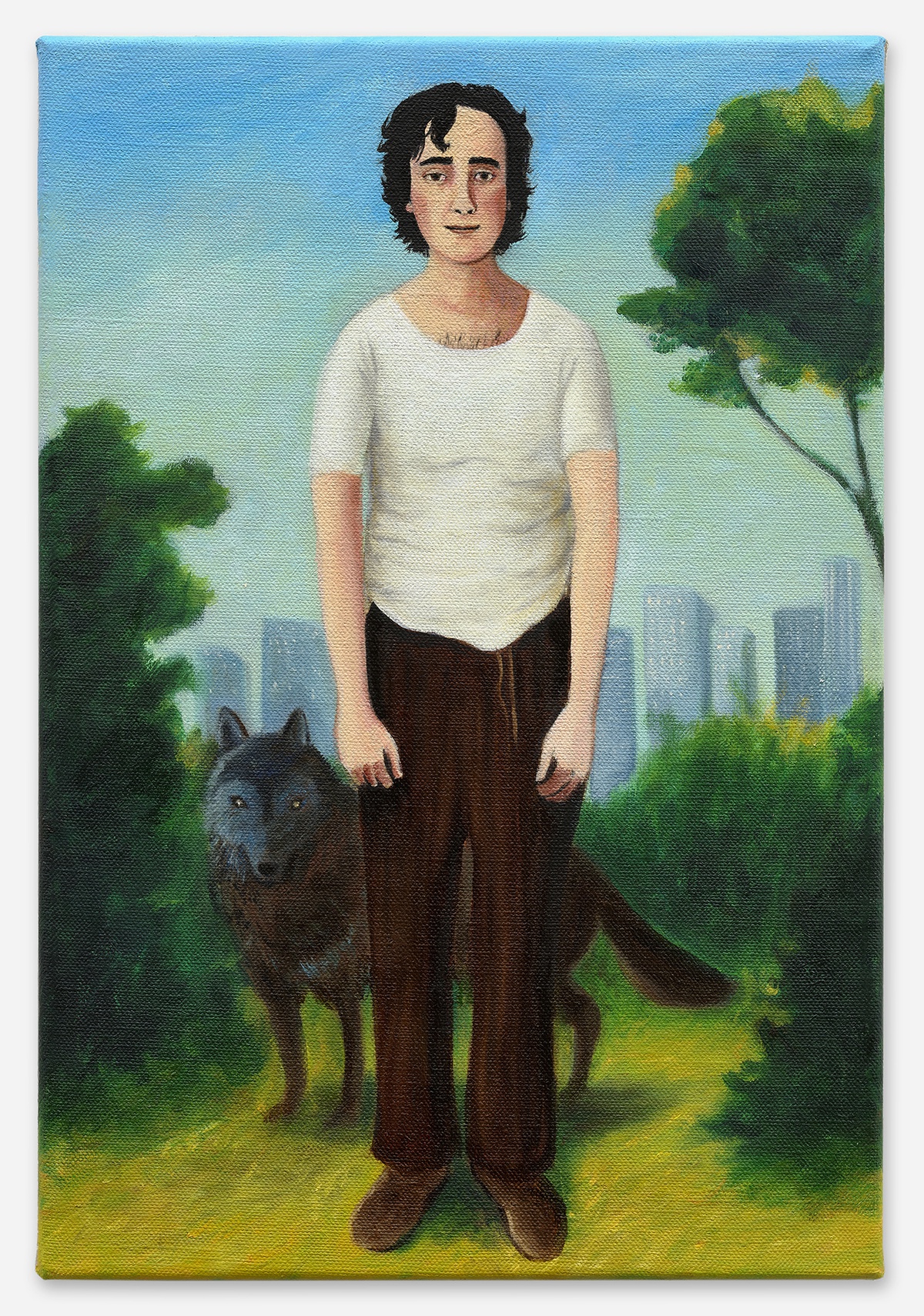

Mathis Gasser, Lazzaro, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

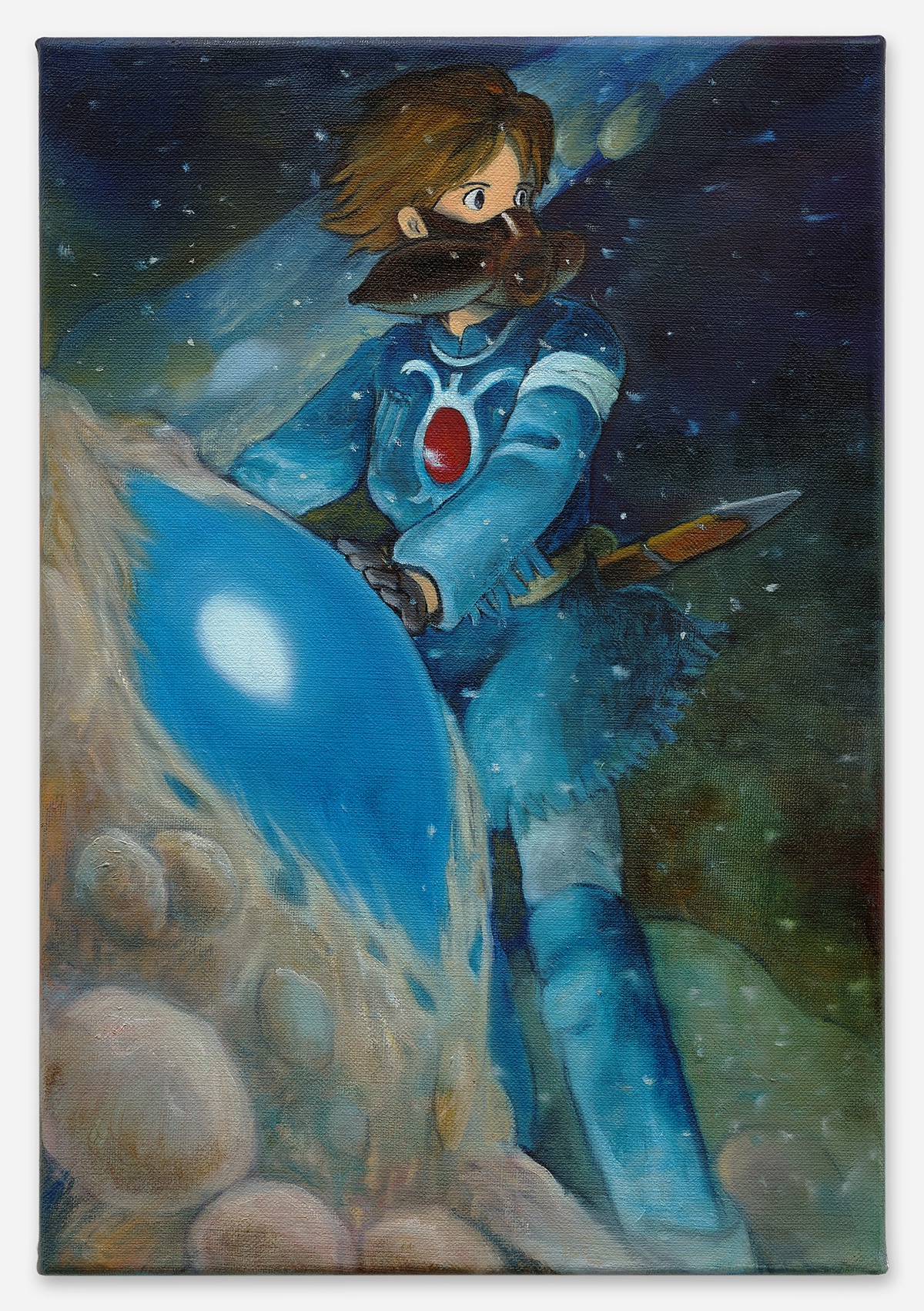

Mathis Gasser, Nausicäa, 2022

oil on canvas

44 × 30 cm

Heroes and Ghosts

At the viewing we glanced across the squat boundary wall at the house next door. Grey pebbledash, sagging net curtains and roof tiles crusted with moss the colour of phlegm. We pictured a retiree, recently widowed. The place had a quiet sadness, its material neglect suggested an occupant preoccupied with elsewhere; another time, another realm. If we knew then, what we know now, would we have moved in?

Detached living is supposed to provide privacy. We don’t share the same sewage pipes, his ceiling is not our floor. We can’t smell his cooking or hear what he watches on telly. But in the space created by this distance a stage is constructed. We neighbours perform a domestic melodrama, visible to each other in ways that apartments, in their modular stacking of lives, are able to conceal.

Our widowed retiree turned out to be a rakish ex-roadie living alone, thin fingers adorned with bulky celtic rings, shorn hair dyed pink, smudged eyeliner and a bouncy gait. At first, he seemed fine, a comforting sort of familiar, the last wiry crank at a private view. He offered neighbourly advice freely, which pubs to avoid and log man to trust, but lingered too long during our encounters as though he couldn’t regulate interaction. He said he hadn’t been sleeping, he’d had a difficult year. Truthfully, we enjoyed speculating, he was our first local character; what did he do in that big old house? What were his desires, his hopes and fears?

Religions tell us we should have ethical responsibility towards our neighbours - Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Love thy neighbour as thyself says the bible, a commandment Sigmund Freud described as ‘still strange to mankind.’ But neighbours are neither friend nor enemy, just people who happen to be near. To scholar Kenneth Reinhard, it’s this troubling ambiguity that produces ‘a zone of indistinction’, contingent alliances slip between hospitality and hostility.

He took pleasure in feeling out the boundaries of our proximity, testing our limits with the help of his dog, a dozy matted collie. Like a canary down a coal mine, the mutt would appear suddenly, slobbering over the ceramic kitchen tiles or taking a dump in the raised beds. Our neighbour was quick to say the previous owner had let him, gesturing at the dog but referring to himself by extension. We were neighbours afterall.

We knew too much about him too quickly. In our first meeting, he’d told us about his estranged relationship with his father. His stories focussed on the ways in which he’d been wronged. He never asked us any questions. Not what we did or even where we’d come from. To him, we weren’t real people with pasts and futures, we were an audience, one that ceased to exist without its star.

So we put in a five bar farm gate, built a trellis to extend the boundary wall upwards and filled a planter with climbing nasturtiums. We tried to create the illusion of less intimate relations. Weeks went by, our plants scaled and tangled around the structure. We didn’t see him. Just his lights, shining down on our lawn through the night, the blackout blind in our bedroom illuminated by a crisp white halo.

Is he in? The woman with set hair, pearls and a royal blue twin-set called from across the fence. We were pulling creeping buttercups and as we stood, sinking our tools into the earth, sweat trickled down our backs. She waved an envelope. Would we witness her serving his eviction, she asked. We squinted at the sun. Fat cat landlord. Had we seen the news, she continued, and got out her phone. As the swallows dived above our heads, she stabbed at the screen and told us about our neighbour.

An indefensible crime, everyone agreed. What to do with men like him?

It was as if the whole village couldn’t take the sealed secrecy of the house any longer; they needed to break its hermetic force.

We didn’t hear the first brick. After midnight. The dog yelped, he sat bolt upright in his bed. Downstairs, plastic blinds blew in the breeze and glass shards sprayed the carpet.

No one deserves to get their head kicked in, we thought, it’s medieval; an angry mob driving out the village rot. ‘Projections change the world into the replica of one’s own unknown face,’ said Carl Jung. Obsessing over certain people fills a defensive function, we don’t want to recognise some part of our own shadow. Best to displace fears rather than face them it seemed to some, the problem extracted, driven out to the edge.

A week later it happened again. By chance we interrupted them. Swinging into the drive, our headlights found two lads crouched down, hoodies pinched tight around their heads, noses poking free. We scrambled from the car shouting, but their young knowing legs hid them quickly. On the floor a giant cobblestone wrapped in a shopping bag shone like a fresh cottage loaf. Adrenaline coursed through us as our neighbour, the root of it all, appeared at the crest of the hill silhouetted by the moon. We saw his hand clench at the lead and the animal brace, ears back. Our first encounter since the landlord. We mumbled something about interrupting someone who hadn’t wished him well and he replied I’m going to have to move, he ran his hand over his head, I haven't hurt anyone.

In a small place like this, a singular crime ripples, who knows when its effects might stop being felt. Was the cobblestone meant for the window or his head? How different those boys' lives might have been if they’d found their target.

The rain thrashed against the corrugated roof when the local policeman sloped into the yard. We said where we’d come from, you didn’t talk to the police. Although we clarified, we wished our neighbour no harm. We’re not taking sides, couldn’t take sides. Never had retribution or restoration felt like such an inadequate binary. He said most of the village agreed, just a few hot headed local heroes. We showed him the cobblestone and he took the plastic bag away as evidence. We didn’t hear from him again.

The landlord refused to replace the window. No point she said, until he leaves, they might do it again and it’s too costly to fix twice. She had her own set of scales, a moral economy.

In the weeks that followed the local hero's response, our neighbour's presence was spectral. He haunted next door, traces of his misery only visible on bin day when the glass collection box overflowed with empty gin bottles. Had he stopped eating? Meanwhile, the weeds grew bigger. A woman with a lanyard walked past one day and asked if anyone lived there. With new eyes we saw how abandoned the house looked.

He reemerged following his court date, like a moth fresh from a chrysalis, paisley print tie loose around his shirt collar. Most of the stuff they found were just pop ups, ‘ghost images’ on the harddrive he called them. Lost on the internet. Stumbled into a place he shouldn’t have been. We stared at his hands as they gripped the trellis, as though we’d already put him behind bars. The headline was misleading, he said, because making and producing meant different things. To download was to make. A technicality, quite different surely, in terms of trauma?

But then no, we thought. The child may not have been next door, but they were behind a door. Someone’s door, somewhere. We looked at the ground. Our jaws clenched. What had we wanted? Remorse?

He said we seemed like nice people, something about his tone implied that could be taken away from us.

Then he lost his job. We started to worry about what he’d do. Family annihilators a friend said, it’s what happens when people lose everything.

He told us he was moving to the city. A Victorian solution this time, let him be swallowed up in the noise and pollution, amongst atomised souls living in urban anonymity, banished to a place with no real neighbours.

We lay awake at night and thought; is this justice or merely a form of human refuse collection? Displacing that which is no longer useful, burying what had started to stink. Could you really restore someone into society by traumatising them? Especially when trauma was the thing that might have caused the crime in the first place?

In the morning, full of empathy, we’d go outside and busy ourselves amongst the rosehips and thistles, trying to catch his eye. In the spirit of rehabilitation we told ourselves to be neighbourly. But before long, as he monologued about all the ways other people were bad and he was good, we’d be praying for him to leave.

Which of course he did, one dank and grey day in early Autumn. Now, as the builders scrape the moss from the roof and pluck the dandelions from the gravel, we spend our time imagining what kind of neighbour we will get next.

–– Naomi Pearce